THE MODERN SHOWER: From Prison Control To Suburban Purity

In 2019 four out of five American homeowners updated their showers if they were renovating their bathrooms. A shower while practical and potentially luxurious does not add considerable value to a house. With so many investing in this technology without obvious potential for capital gain it begs the question, why? What follows is a brief and narrow history of the evolution of the Euro-American shower and an overview of new shower solutions in art, cinema and the home.

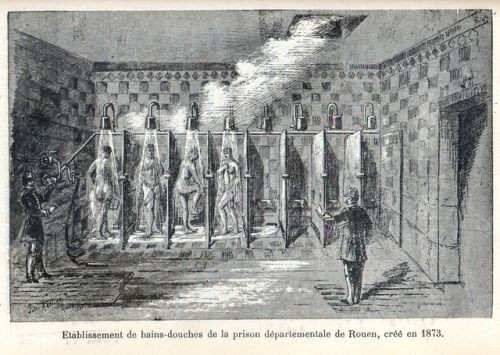

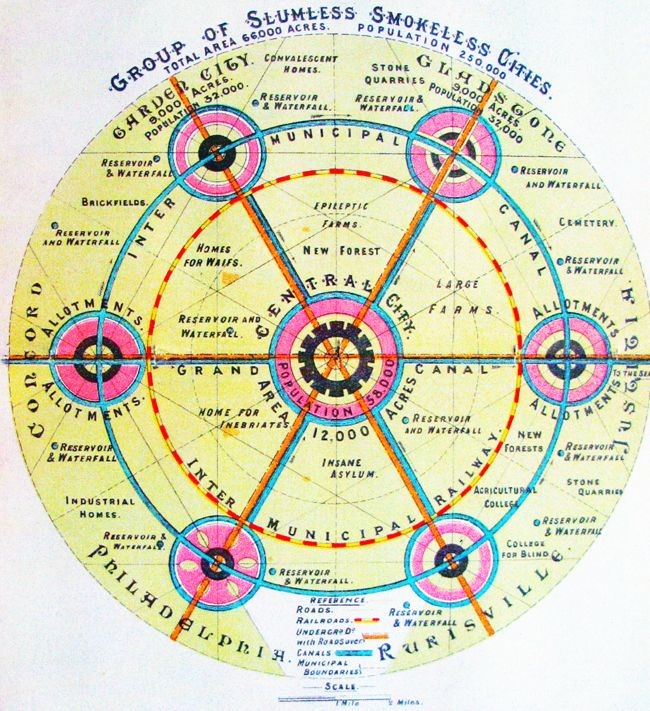

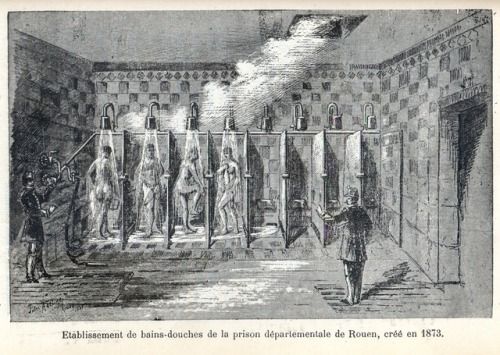

In 1767, William Feetham invented the first mechanized shower. Originally a stove maker, Feetham’s shower had a lukewarm reception as it recycled the same water it heated, meaning the water became increasingly dirty as one bathed. Over the following decades the design of the mechanism was enhanced, but it didn’t gain popularity until Dr. Merry Delabost, a French physician, designed the first mass showers for the Rouen prison in 1872. Lined up as if cattle en route to slaughter, these rows of shower stalls acted similarly to prison cells. The shower held the naked (male) prisoners as captives for easy surveillance. Structural transparency was done in the name of cleanliness. The gaze of the guards became a cleansing agent in and of itself: to be watched meant to be controlled, to be controlled meant to be clean.

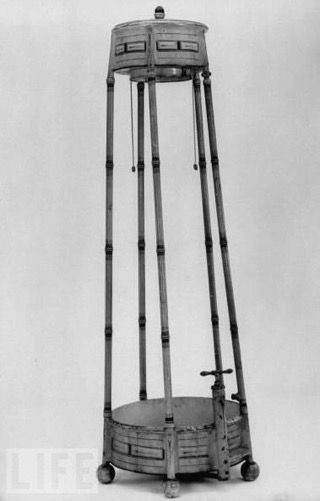

Thermal shower in an asylum, France (1880). Courtesy Anders Wiggström.

Perhaps it is the shooting spurts of water that felt too obvious an innuendo, but at first upright showers were considered the domain of men and deemed improper for women. As showers slowly left the prison, they found their way into gymnasiums and army barracks. But the ability to survey, dominate, and potentially subdue via the mechanism made them popular in an unlikely location: psychiatric hospitals. Throughout the late Victorian era, a cold “shower-bath” was seen as an excellent treatment for psychosis and more specifically, hysteria. Suddenly the shower became an acceptable location for women, as it was deemed a treatment for the unruly. Beyond the reportedly therapeutic qualities that cold water held, the shower-bath became a symbol of cleansing a “disease” that was beyond skin deep. Dirtiness became a metaphor for the madness of the hysteric and dousing them with freezing water, allowed for a symbolic cleansing of their deviance.

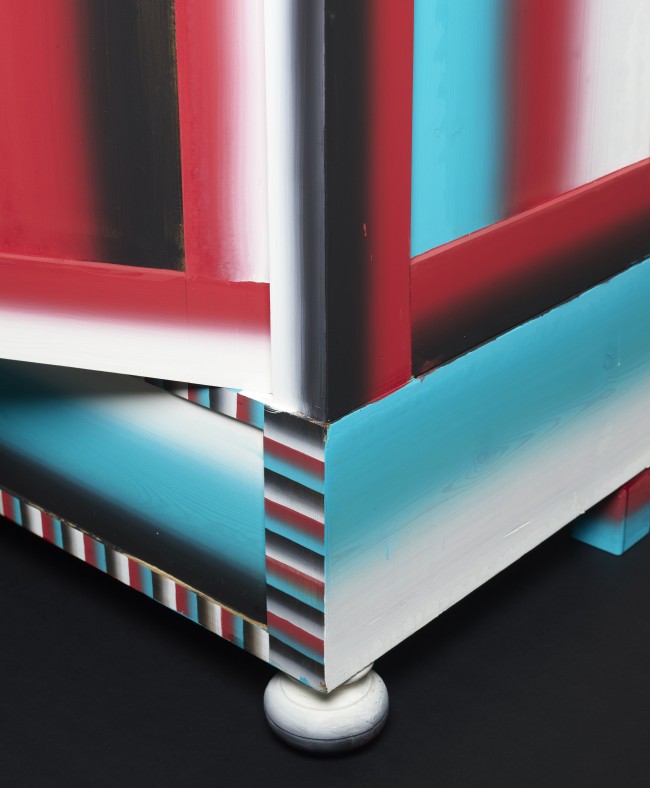

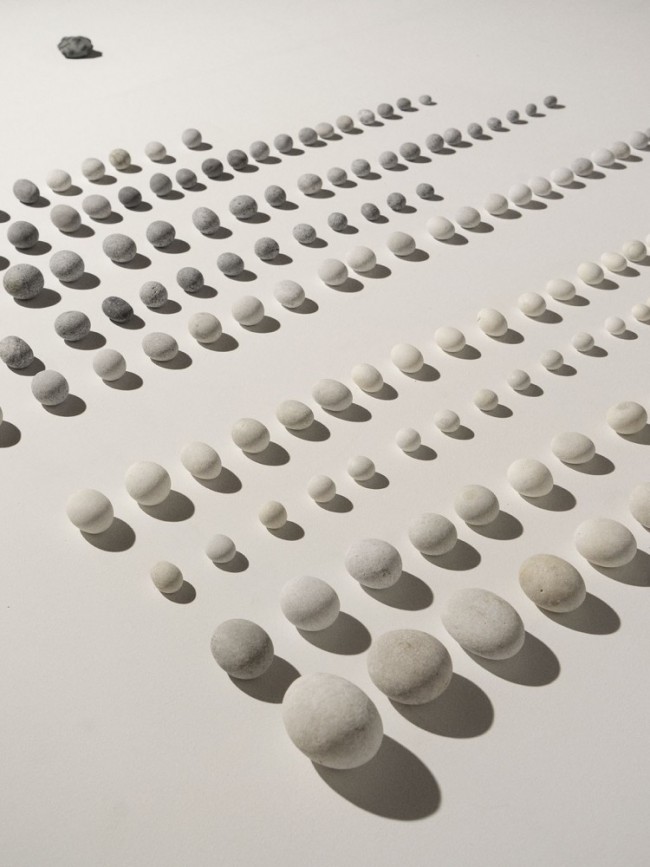

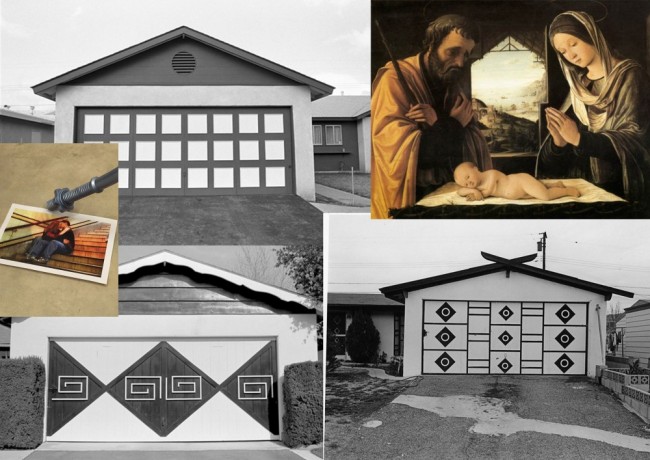

Untitled by Hans-Christian Lotz (2017). Courtesy Christian Andersen Gallery.

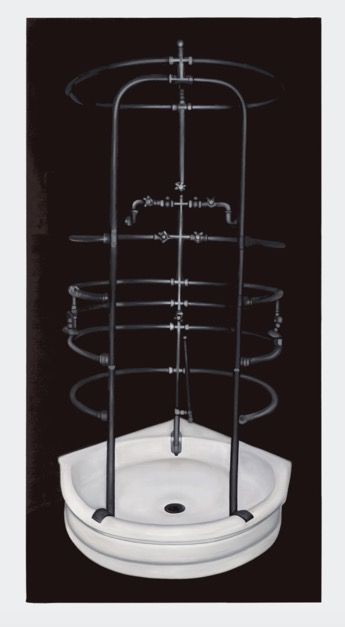

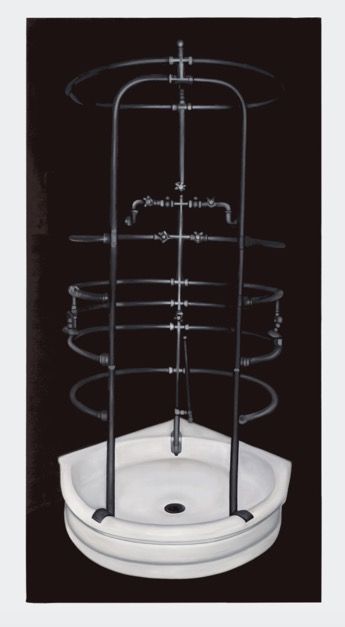

While the popularity of the shower proliferated in communal spaces by the early 20th century, domestic showers were still relegated to the wealthy, and let’s presume, white, homeowners. The form saw variations such as the therapeutic rib cage shower which shot water on the kidney, the liver, neck, and heart. The rib cage showers depicted in painter Megan Marrin’s recent show Convalescence recall the history of the shower’s use as a place of recuperation and as a wellness treatment. Marrin's showers are illustrative skeletal forms, each offering a slightly different configuration as if to suggest they could be inhabited by disparate bodies, or treat to altering ailments. The paintings of these vintage apparatuses reference the hysteric’s shower, a place of containment and decontamination, a holding chamber for a body that refuses to be seen. Just as asylums and prisons prescribed showers as treatments, so too did urban epicenters begin to deploy them. Visible grime became a way to not only judge a person's social position but to plumb the depths of their morality. In The Battle with the Slum (1902) Jacob Riis, social reformer would write of the new public baths in New York that, “soap and water have worked a visible cure already that goes more than skin deep. They are moral agents of the first value in the slum.” Bathing became a way to absolution with the potential to pierce not just the skin but the soul.

-

Megan Marrin's Convalescence from David Zwirner Gallery's Platform: New York (2020). Courtesy Queer Thoughts.

-

Megan Marrin's The Regimen from David Zwirner Gallery's Platform: New York (2020). Courtesy Queer Thoughts.

To be dirty means to stink and having a strong odor has long been associated with the disreputable cc: putain, French slang for whore, which comes from the latin putida, meaning stinking. In artist Puppies Puppies’s 2016 show at Balice Hertling in Paris, a domestic shower was placed in the corner of the gallery space, “available to anyone who would like to use it.” Installed for the public, this domestic shower was used by a go-go dancer during the opening. A clear reference to Felix Gonzalez-Torres Untitled (Go-Go Dancing Platform) (1991), in Puppies’s piece the dancer’s presence allowed for viewing their potential “purification” and yet, once inside the shower, they left it sullied for whomever used it afterwards. Additionally it creates a direct relationship to a queer history of disease and cleanliness as Gonzalez-Torres intial piece was made to reflect on loss during the AIDS crisis. While Puppies’s shower may have been a democratic proposition, by watching the dancer wash it easily illustrated the tenuous boundary between purity and defilement creating new divisions between the moral economies of power and consumption.

Over the course of the next 40 years, the home was restructured around the availability and storage of water, gas, and electricity. By the 1950s and 60s, the upright shower was ubiquitous in the American home and had replaced the reclining bath as a cost and time efficient measure for landlords and homeowners alike. The shower, now standard, entered into the cultural imagination as a location to prey upon the “polluted” gender. In Hitchcock’s Psycho, the shower acts as a kinky semi-transparent enclosure designed for the voyeur to watch and creep up on a soaking wet, vulnerable Marion Crane. Since this iconic scene, the shower has become a trope deployed in countless horror films through the latter half of the 20th century. From Slither and Arachnophobia to Nightmare on Elm Street 5: Dream Child the increasingly independent women of the late 20th century horror frequently has found themselves subject to erotic conquest as they are assailed by a penetrative force while showering. Forever existing as a periphery, the suburban backdrop of these films is entrenched in a racist history of practices like redlining which left many suburbanites in a constant state of anxiety around the potential invasion by outsiders. Thus the proliferation of shower scenes in horror films exist as an allegory for the white suburbanites' fear of contamination.

Showers in Dr. Delabost Rouen Prison, France (1873). Courtesy HSL Special Collections.

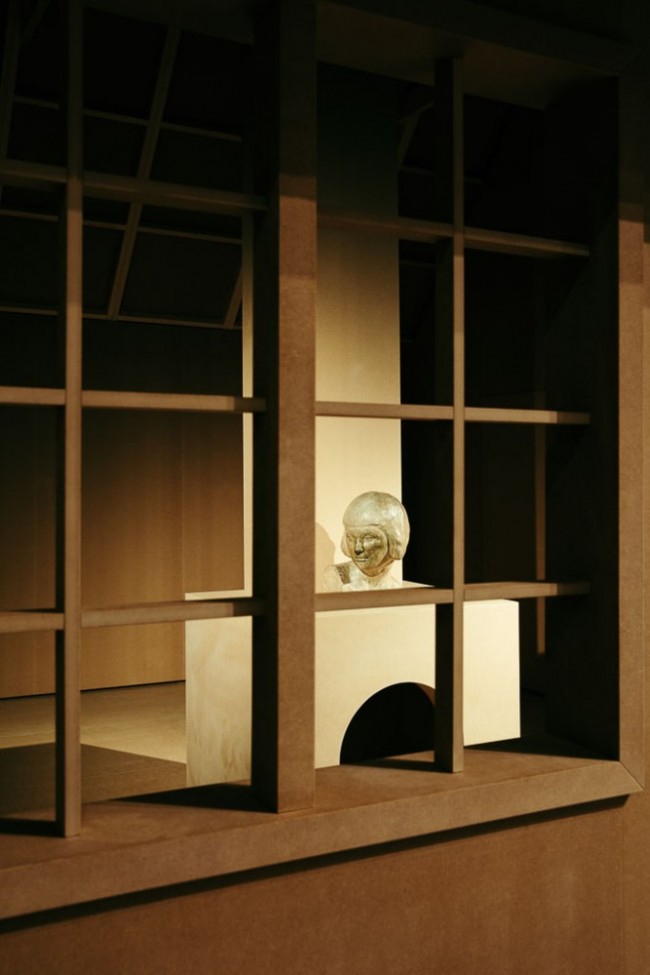

The horror of the shower is no better illustrated than in artist duo KAYA’s installation at the 2017 Whitney Biennial SERENE, which in addition to a series of large painted “body bag” pieces included three cast-resin showers. Beyond the association of the shower with extermination, the scene as a whole reads of pollution and decay as if a psychedelic trip down the drain. KAYA took the white tiled space of the shower and substituted opaque swirling dark purples, pukey greens, and browns making it impossible to measure one's progress in self-decontaminating. The final sculpture in the installation, a free-standing piece consisting of a large semi-enclosed rectangle covered in colored tile, exists at once as a folded up subway platform and as a claustrophobic bathroom.

To be clean, means to be unadulterated, refined. It means to be pure. In Dana Berthold’s “Tidy Whiteness: A Genealogy of Race, Purity, and Hygiene” (2010) she explains purity as a concept inextricably linked to white supremacy as white has come to symbolize cleanliness: just think of white linens, white houses and white porcelain. The idealized tiled bathroom is not white because it helps to keep track of grime, but because it indicates a figurative shift into a space of complete control. Control is the very essence of cleansing practices as cleaning seeks to exert force over an external and mostly invisible chaos i.e dirt and germs.

SERENE 2017 by KAYA (Kerstin Brätsch and Debo Eilers) from the 2017 Whitney Biennial. Courtesy ArtMag by Deutsche Bank.

Frequently portraying queer black men in moments of self-care, Jonathan Lyndon Chase’s 2019 painting Man in Dirty Shower shows a man showering as oversized tear drops of water cascade around him. The shower curtain matches the tone of the showerer’s upper body obfuscating foreground and background. Lighter scrawls delineate the man’s arm and hand from shower curtain pleats. Towards the bottom of the painting, the legs of the subject are represented in outline, filled with the same white of the shower basin as if to suggest the two are no longer separate. By rendering the shower curtain and bathroom in black, this work contests the whiteness traditionally ascribed to the location as subject and object seem to seep into one another. In the end, Jonathan Lyndon Chase’s painting exposes how the aesthetics of hygiene and language of cleanliness are insidiously linked.

In addition to race, the shower speaks to class. Long before Trump was infamously outed for enjoying a douche d’or, Washington already had a fixation on the shower. “Showering after work” is a populist phrase utilized by American politicians to relate to blue-collar workers. The assumption is that if you shower in the morning, you work a desk job and, it would be inferred, are paid more than those who shower in the evening after working some form of manual labor. For example, during the 2008 financial crisis, the Bush Administration’s bailout focused on Wall Street and big business rather than unions. In turn, they were swiftly criticized for prioritizing “those who shower before work, but not those who shower afterwards.”

SERENE 2017 by KAYA (Kerstin Brätsch and Debo Eilers) from the 2017 Whitney Biennial. Courtesy The Humble Fabulist.

Class is lathered into more than our hygienic protocol; it is layered into our products. For example, soap, an ancient invention, highlights social inequality in the bathroom. It took until the early years of WWI for scientists to derive cleaning solutions that were not based on animal or vegetable fat. These new solutions were based on petroleum byproducts and are known today as detergents. The most commonly used “soaps” are usually detergents as they are cheaper to produce. Unfortunately, many detergents are carcinogenic. As much awareness has grown around the adverse effects of these solutions, those who can afford to turn to natural products which on average are ten times more expensive than generic brands. Take Goop’s offerings of natural body wash and scrubs that are 20 to 30 dollars, whereas cheap brands with known carcinogens cost on average 2 to 3 dollars.

The intricacies of shower product politics are further explored in Hans Christian Lotz’s shower caddy sculpture. The work was first installed in a corner of Christian Andersen in Copenhagen and consists of a shower caddy filled with the organizer’s empty or half empty bottles of body wash, cleanser, shampoo, and conditioner. When installed, the work reads as a portrait that exposes its subject not by figuration, but by product selection. This in turn allows for one to infer not merely class but also taste. For example, Dr. Bronner’s suggests a lifestyle dissimilar to Byredo users while Aesop indicates an entirely different tax bracket from those who shop at CVS. Luxury, wealth, aspiration, it’s all ingrained within the subtle selection of gels and scrubs that we use to get clean.

In recent renovations, the most popular trend in shower design is known as the “open concept shower.” Here, the shower which historically managed the aberrant is more or less dematerialized. The open concept shower is essentially only identifiable by showerhead and drain otherwise the space has little differentiation between the other bathroom areas. Without structural confinement, the shower is proposed as an immersive, free experience. As we move from a culture of patrolling individual hygiene to public health, the seamlessness of the open concept shower fails to hide the history of the shower as a cell, a voyeur’s trap, and a cage because we are forced to police our own bodies rather than rely on externalities.

Olivia Erlanger is an artist and writer based in Los Angeles. She has shown internationally at Motherculture, Human Resources, AND NOW, Pilar Corrias, and Mathew Gallery. She received the inaugural BMW Open Work Frieze Prize in 2017.

Images courtesy the author.