BASIC INSTINCTS: How Instagram Is Changing The Way We Decorate Our Homes

Today’s interior-design trends are not the culmination of some artistic commentary on contemporary society like Constructivism or Art Nouveau. They are a reflection of the online spaces we’re conditioned to spend time in — aesthetics that look good on social media.

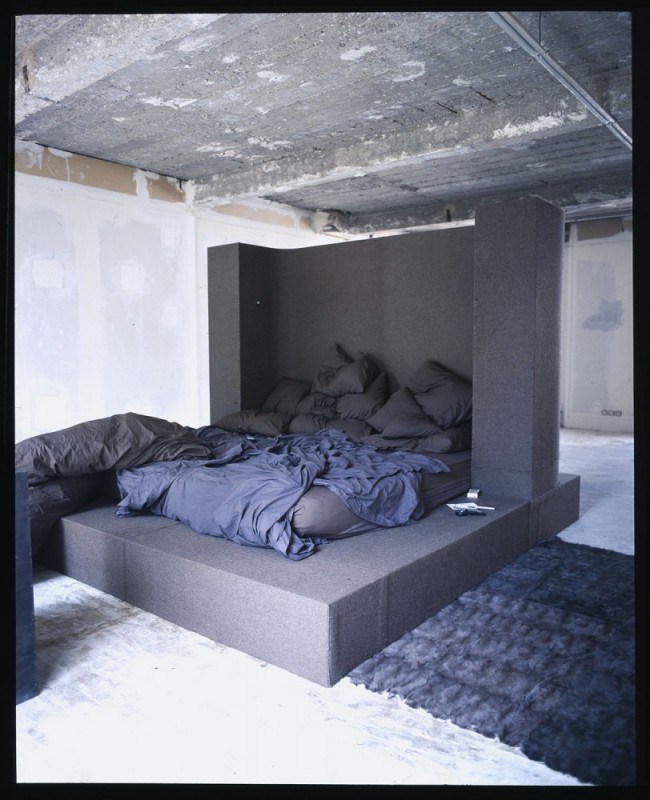

If Postmodernism is the cultural logic of late capitalism, then Instagram is its apogee, a place where trends go to die, only to be reborn moments later. On platforms like Pinterest, once-rare images of over-designed loft spaces featuring cantilever chairs and low-slung leather sofas are scanned, uploaded, and funneled into Tumblr blogs and Instagram mood-board accounts like @__dreamspaces, @decorhardcore, and @casacalle_. In turn, these online curators create new desires for old aesthetics by turning reference photos into vessels for boosting engagement. Such accounts become producers, or rather, regurgitators of culture — inspiring consumers to mimic what they see online in their own homes as a means to earn likes. That’s why we see Mario Bellini’s bubbly, oversized Camaleonda sofa all over Instagram, and endless streams of teens lounging on knock-offs of Marcel Breuer’s Wassily chair on TikTok. In a hyper-visual world, the most relevant trends are those that stand out on a small screen.

Thanks to social media, collecting easily identifiable designer furniture, or replicas of it, is no longer a highbrow intellectual endeavor but an attention-seeking game that anyone can play. Click on any furniture-resale account in the greater New York area and you will find links to countless profiles hawking the same grammable goods: Spaghetti chairs by Giandomenico Belotti; Chiclet sofas by Ray Wilkes; Componibili storage units by Anna Castelli Ferrieri; and a seemingly infinite supply of Lucite Plia chairs by Giancarlo Piretti. For those who approach home decor from a purely aesthetic standpoint, the popularization of vintage furniture on Instagram has opened the door to design history, or at least the idea that furniture can retain value and intellectual significance beyond its functionality. For the average consumer, Instagram furniture resellers offer an appealing alternative to the numbifying aesthetics found at contemporary retailers like West Elm or CB2. But for those who consider themselves experts in the field, this so-called democratization of taste has destructive potential. Not only do vintage dealers hawking Mies van der Rohe and Marcel Breuer make items from certain designers more expensive and harder to source, they also, according to aspiring gatekeepers, threaten the relevance of lesser-known designers altogether.

I have friends in their mid-20s who act as if they discovered 80s Postmodernism long before anyone on Instagram did. They curse the rising costs of vases made by Czech designers and mock those willing to pay exorbitant prices to vintage dealers for chairs by Gaetano Pesce. Similar critiques of design newbies proliferate in tweets and memes that point to the increasing ubiquity of Cesca chairs (Breuer again) and selfie-friendly Ultrafragola mirrors (Ettore Sottsass) found on the feeds of models and influencers. These memes, accessible to anyone who spends time looking at interiors on Instagram, elicit elitism, but they also make those with minimal design knowledge feel as if they too are in-the-know. All of this has led to a democratization of design history (the more posts, the more awareness), while enabling the masses, regardless of their economic status, to poke fun at the poor taste of celebrities and their peers (lest we forget Gigi Hadid’s self-designed New York apartment, or Kimye’s monochromatic McMansion). The result is a confused mish-mash of design-adjacent people competitively one-upping each other online, leading to a thirst for obscure gems from yesteryear, and an increase in gatekeeping surrounding design and curatorial practices.

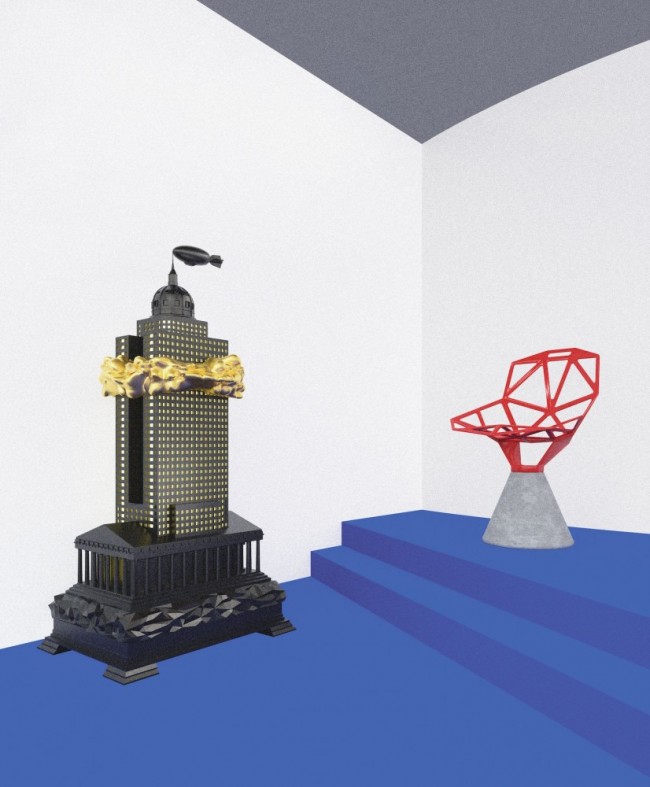

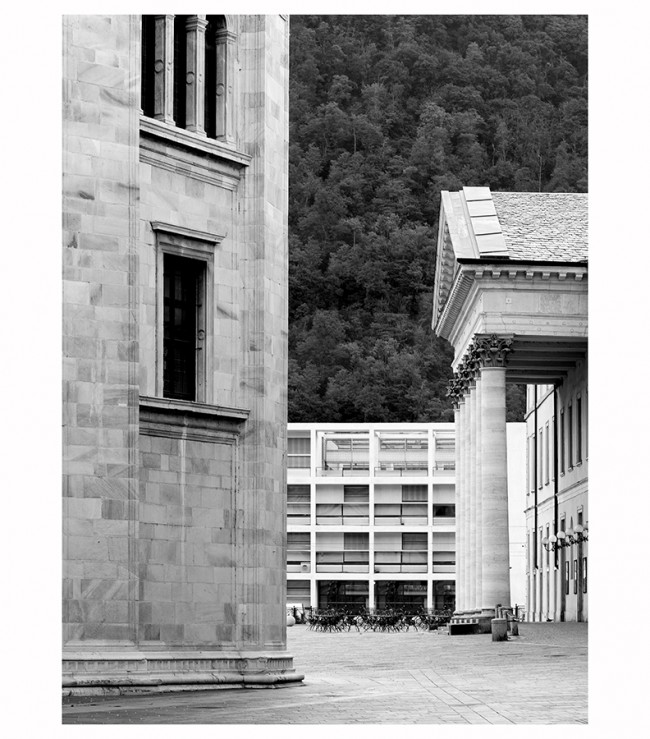

Take the recent uproar surrounding the newly-designed Parisian headquarters of luxury French fashion label Jacquemus. The space, art-directed by Simon Porte Jacquemus himself (note the absence of the word designer), incorporated some of the hottest vintage furniture du jour: a Camaleonda sofa (recently re-issued by B&B Italia), a Mississippi couch by Pierre Paulin, and chairs by Marcel Breuer (again!). But along with a slew of press (and regrams) praising the project were a series of viral Instagram posts from industry insiders who claimed that some of the custom work featured at Jacquemus HQ was directly copied from past and present architects (the catalyst was a chrome desk that mirrored a 1932 interior by Hans and Wassili Luckhardt). Why am I dredging up this months-old Instagram drama? Because it illustrates the complexities of clout-based design, and how both class and generational divides complicate current design trends. For fashion fanatics and design-adjacent consumers, the project was a bloggable reprieve. But to industry watchdogs, it was an example of Instagram aesthetics gone awry, the result of a culture that favors curation over original ideas, and enables the wealthy to earn clout merely for collecting consumer goods.

In today’s hypervisual world, it’s almost foolish to claim originality on any given creative endeavor. Not only is almost all art and design built on references, but, in the age of Instagram, most of the references we see are the same. For some, this is a call to work harder, to log off the Internet and find more obscure books to scan, or at the very least to take special care to give credit to those who inspire your work. But for a younger generation who have grown up with the Internet and social media as their main, if not only, creative resource, it’s not originality that counts but curation, and whether something looks good on the feed. It’s the reason why gen-Z TikTokers don’t care whether or not the Wassily chair they’re lounging on to show off their latest fit is authentic, or if Jacquemus copied the styles of other designers, dead or alive. In the era of social media, architectural entertainment supersedes intellectualism, and regardless of callouts and cancellations, it’s unlikely this will change.

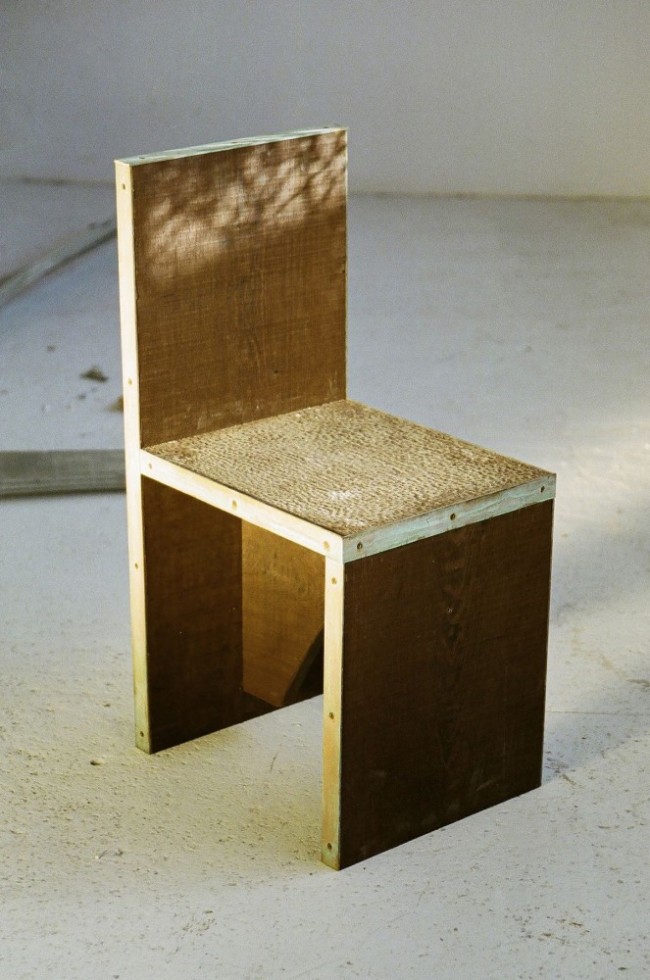

So what does this mean for design? Whether we like it or not, we’re stuck in a Postmodern cycle of boom and bust trends dictated by whichever media hold the most influence over how information is disseminated online. But this doesn’t mean that tastemakers are totally obsolete. While we were bickering over art objects on Instagram, the real gatekeepers of the design world were busy collecting craft-focused pieces that spoke to the issues of the Anthropocene in a way that popular Postmodern aesthetics cannot. Yet, in an ironic twist of fate, the small wooden stools crafted in response to the maximalist, attention-seeking decadence of social-media-inspired interiors ended up being the most Instagrammable of them all.

Text by Taylore Scarabelli

Taylore Scarabelli is a New York City-based writer, consultant, and co-founder of Relevant Community. Her work has been published in New York Magazine, Artforum, Kaleidoscope, Vestoj, and more.

Images courtesy of @ambience.jpg, @chrissyteigen, @homeunion, @camaleonda.love, @projects_and_things, @jacquemus, @rinalovko.studio, @ultrafracciolo, @alexandraposterbennaim, @placesandspacesinnewyork, @julie.fi, @18.01london, and others.