ARCHITECTURE AND CONTAMINATION: An Interview With Andrea Bagnato And Ivan L. Munuera

In the context of public health, architecture is often understood as the construction of physical spaces for shelter and healing, and the eventual management of disease. It is less critically recognized for its role in creating the environmental conditions for a disease to form and spread. And yet, architecture has played and continues to play a crucial role in mediating the relationships between humans, as well as between humans and other species, impacting for example how malaria spread in the early 20th century and how the HIV/AIDS crisis was instigated in the later part of the century.

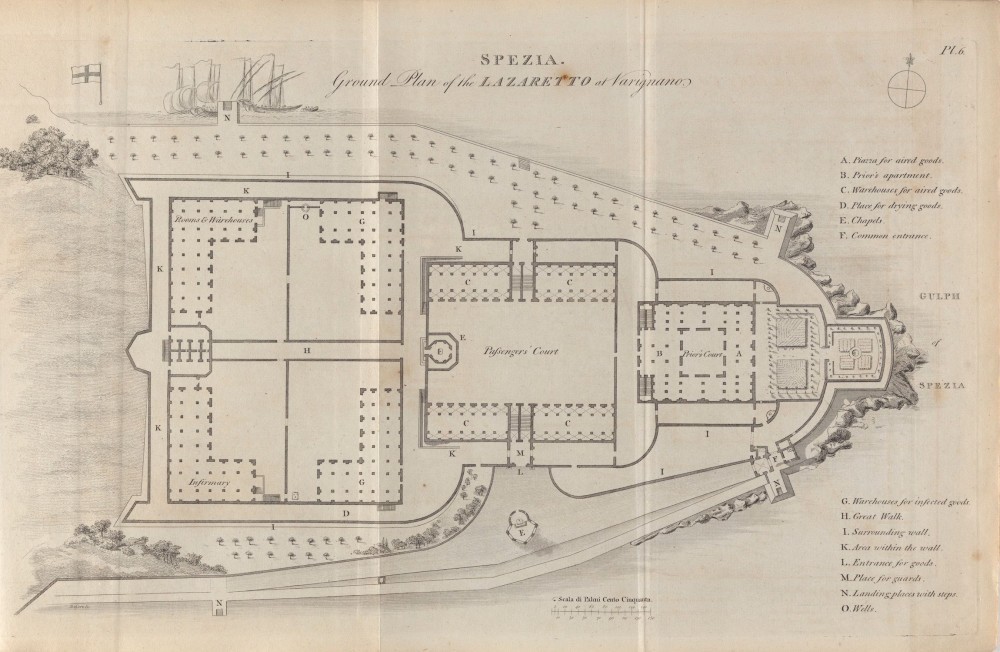

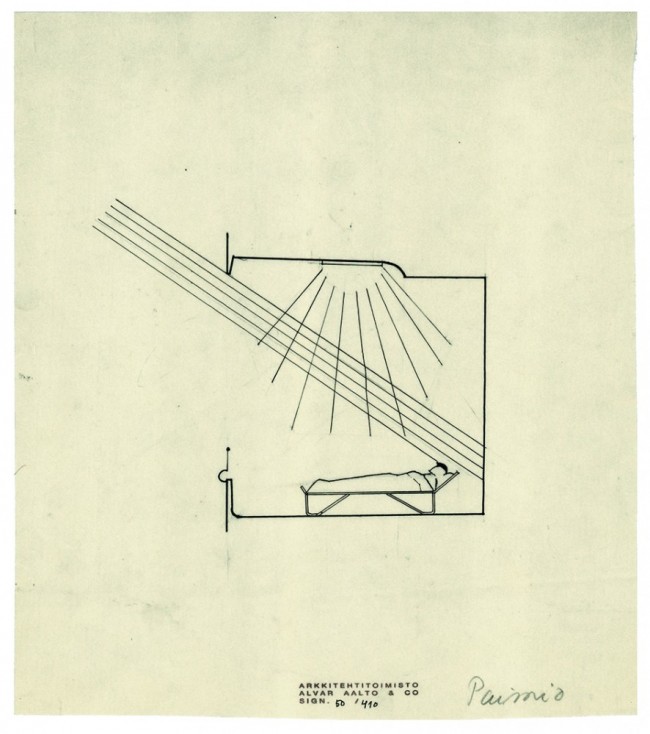

I was introduced in greater depth to this link between architecture and disease as part of my work helping to organize MoMA’s R&D Salon series led by Paola Antonelli. A program on the subject of contamination was scheduled for this past April, ironically put on pause due to the very subject of its inquiry. My research on contamination had led me to Andrea Bagnato’s long-term Terra Infecta project on the architecture and ecology of infectious diseases, Ivan L. Munuera’s writing on the “discotecture” of architectural spaces during the HIV/AIDS crisis in New York in the 1980s, and their joint research into the histories of urbanization in the US and the UK and the subsequent rise of Lyme disease.

Last month, as I entered my sixth week of coronavirus lockdown, I was curious to learn more about how this research informs our current moment. Sheltering in place at my New York apartment, I Zoomed with Bagnato in Milan and Munuera also based in New York to discuss the wider role pandemics have had on urban society and how these histories can inform architects how best to approach design in a post-COVID-19 world.

Empty seats outside a bar in Milan during aperitivo hour. Coronavirus lockdowns have stalled normal urban activity. Photography by Andrea Mantovani

Samantha Ozer: Ivan, much of your work has been related to the HIV/AIDS crisis in 1980s New York. Considering that gathering can only happen in the digital space now, can we conceptualize this pandemic in relation to that historic moment?

Ivan L. Munuera: One of the aspects that was highlighted during the HIV/AIDS crisis was that activism could only happen through information. And the correct understanding of the management of information. Misinformation as we are seeing now with coronavirus is incredibly dangerous. One of the most outrageous cases might be in the UK with Boris Johnson saying that nothing is going to happen. Or all around the globe, leaders are framing the crisis as a matter of individual responsibility, and not a collective one supported by protocols, economic help, universal healthcare etc. The idea that we have to make this personal, that we have to take ownership of the epidemic as opposed to a governmental effort to provide support is reminiscent of a dark history.

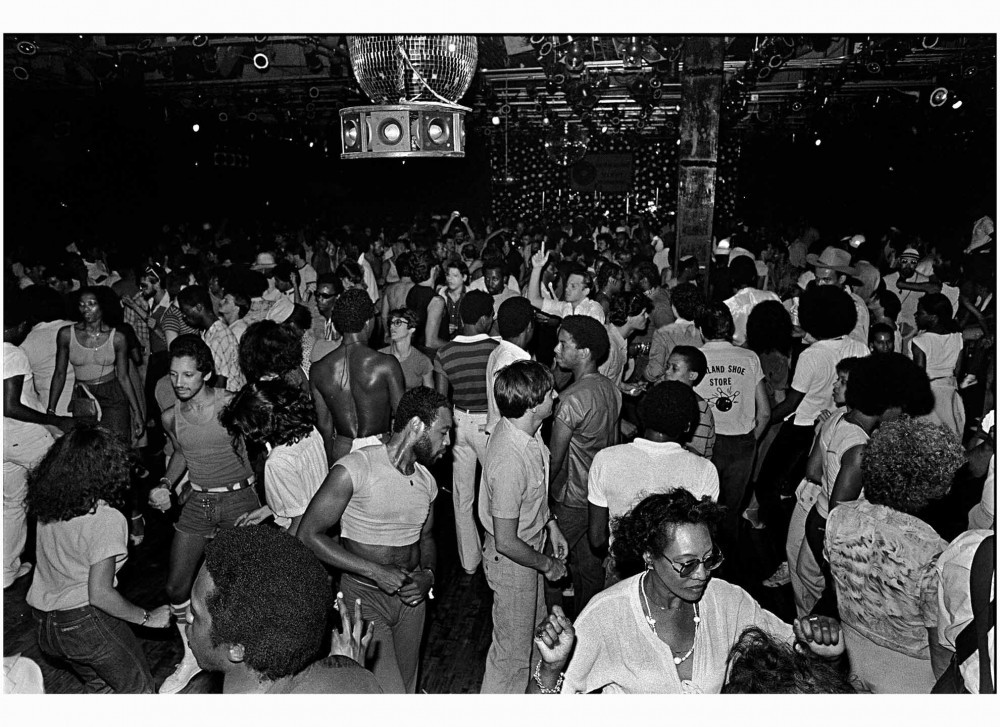

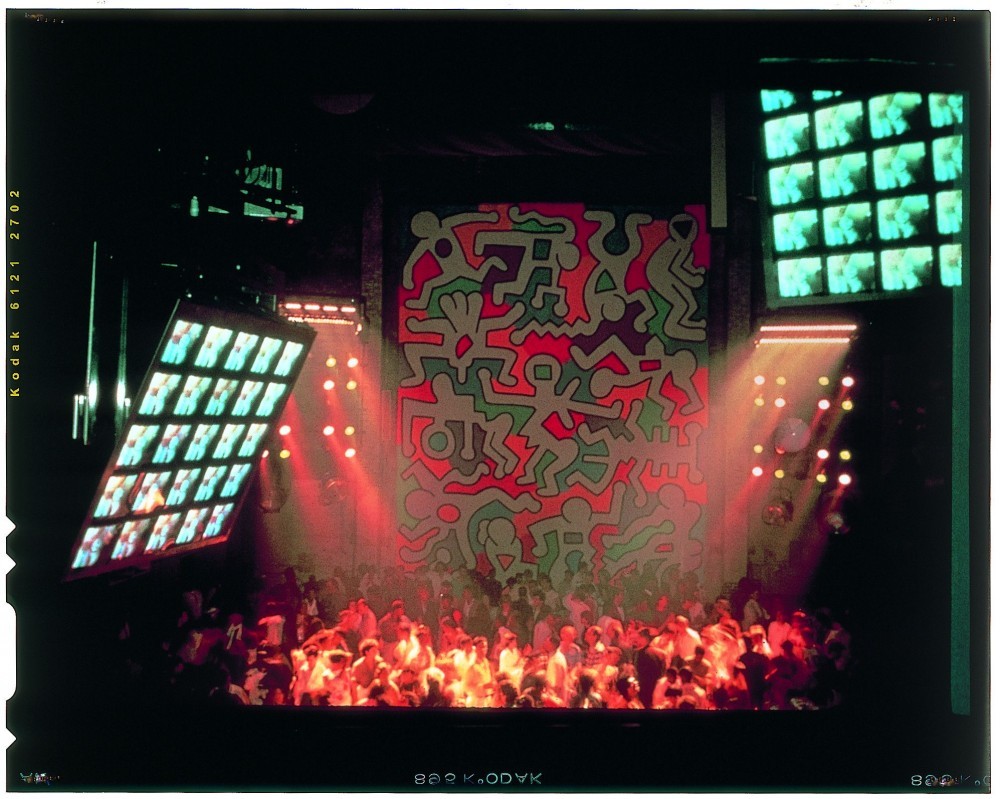

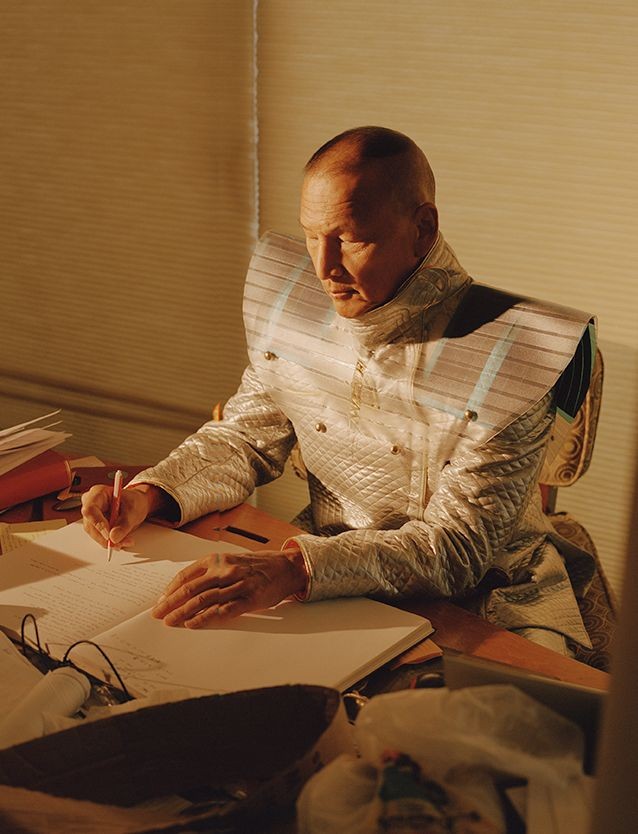

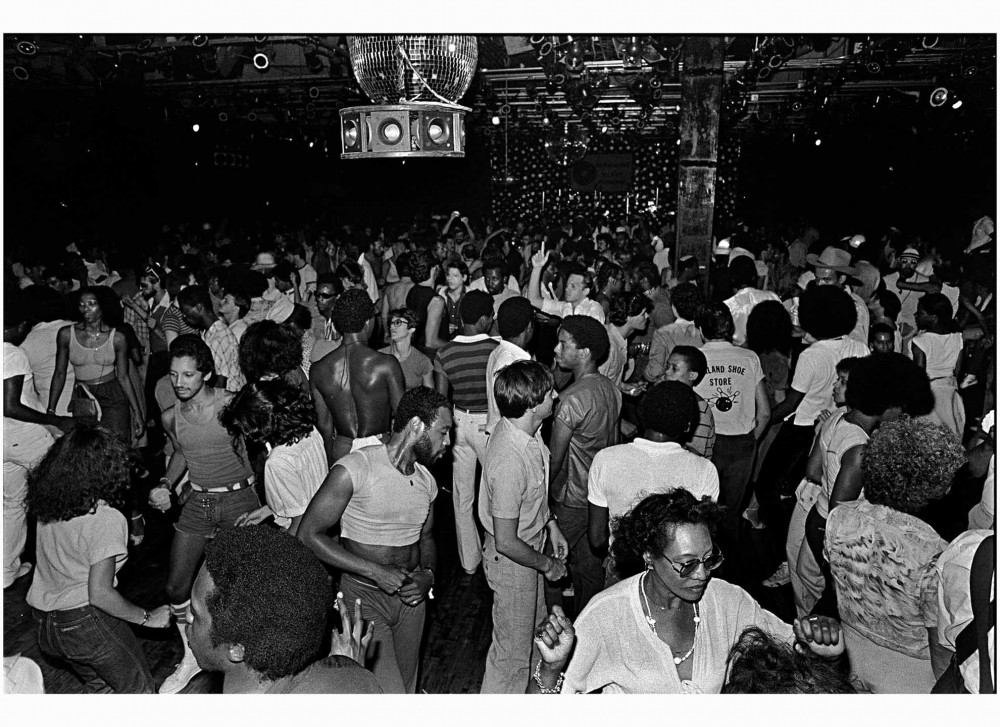

Between 1977 and 1987, the Paradise Garage, at 84 King Street, was one of the most important and influential clubs in New York City, its devotees predominantly black gay men. Photography by Bill Bernstein

This idea of blame and a personal, moral responsibility for one's health is interesting. Where we saw with the HIV/AIDS crisis, doctors referring to a “gay lifestyle” as the cause for disease, U.S. Surgeon General, Jerome Adams is urging people of color to “refrain from drug, tobacco and alcohol abuse” as they are "socially predisposed to coronavirus.” This notion of self-regulation is troubling.

Andrea Bagnato: In Italy, the issue of blame dovetails with an existing narrative. Particularly since the 2008 financial crisis, there was a very marked securitarian shift in the political discourse. The presence of people in the streets at night started to be seen as a threat, especially of youth and people of color gathering outside. So during the current lockdown we are now seeing a great number of police going after nonwhite people. They are often refugees who live in temporary centers — a walk outside might be the only personal space they have.

In relation to the history of HIV/AIDS, this moment is unique in that sociality has been suppressed and even seen as something to blame. Now, in the talks of re-opening, sociality is never part of the equation; the calculation that is being made is only based on the economy and on production. This passing over of the importance of social life, of gathering in person, is of course a counterpart to the fact that actually the lockdown is framed in purely capitalist terms. While everyone needs a social life, staying in the home becomes more of a problem for certain groups for whom “home” or “family” are not welcoming spaces.

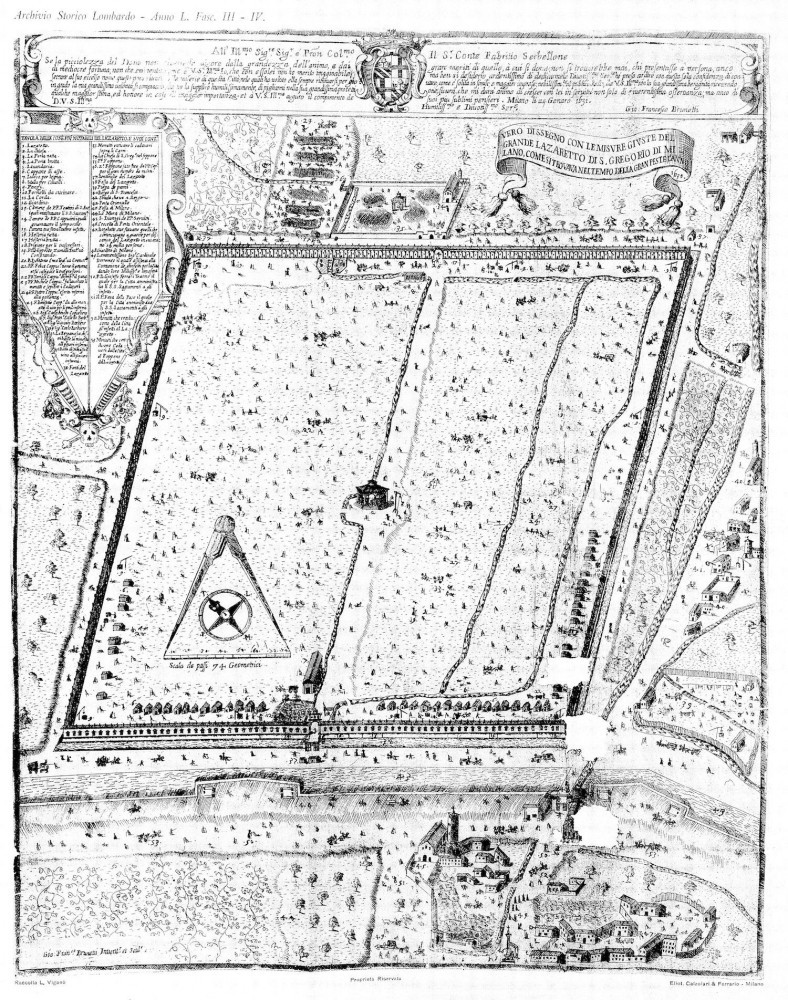

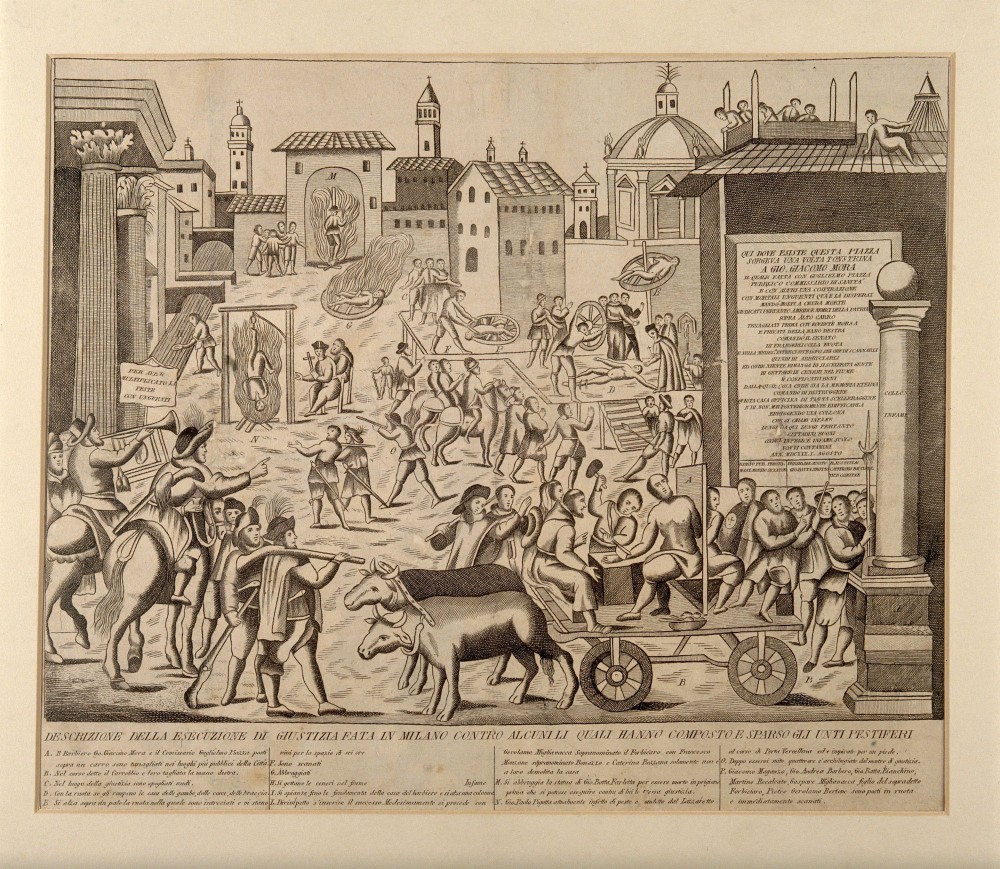

The engraving tells the story of the torture and execution of several untori — people suspected to have intentionally spread the plague — during the 1630 epidemic in Milan. The home of one of them, Gian Giacomo Mora, was razed to the ground and replaced with a monument, called colonna infame, meant to discourage the population from any such behavior. This event was the subject of a detailed critique by Alessandro Manzoni in his eponymous 1840 book. Courtesy Wellcome Library

As we consider the different ways this epidemic is felt across communities, how do we define a public and the boundaries between public and private space? Who constitutes the mainstream?

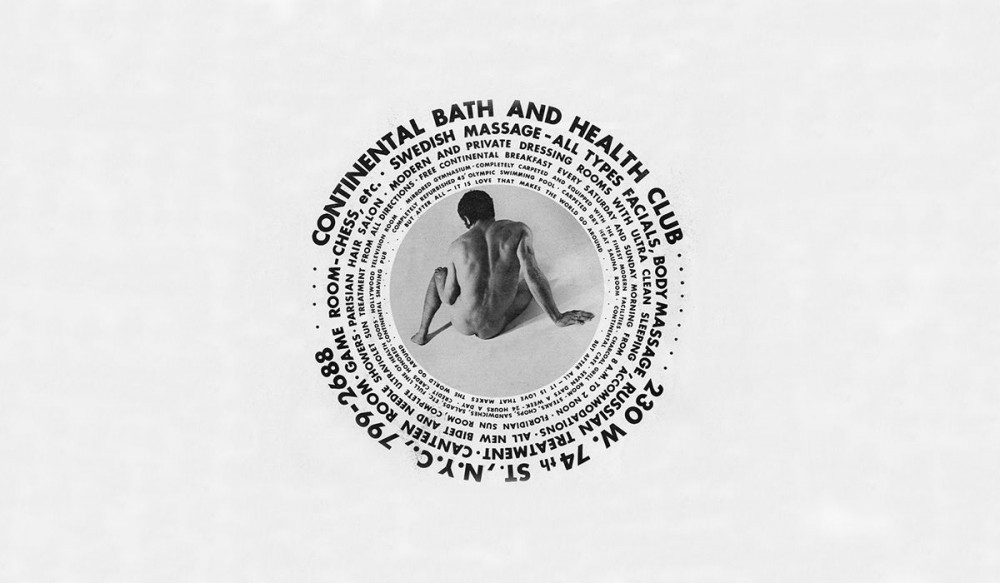

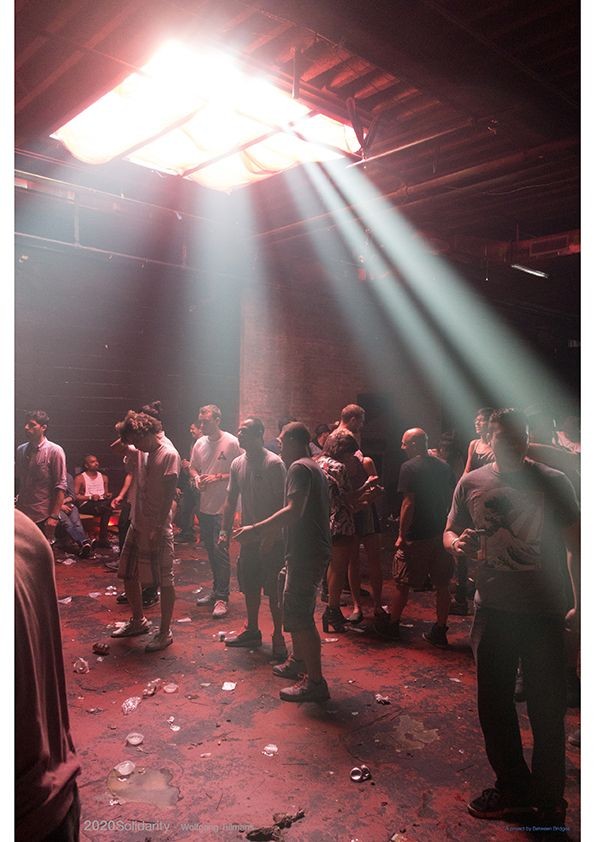

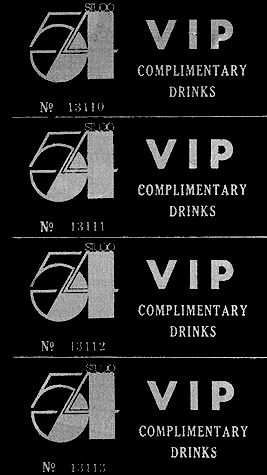

ILM: During the HIV/AIDS crisis nightclubs and saunas were activated as physical spaces where not only the LGBTQ+ community, but everybody, was welcomed. Nightclubs provided a space for information and discussion. They were also places where many different kinds of people could gather and form a very intersectional and interracial kind of activism. These private spaces served as homes for non-heteronormative families and were felt as a public space that allowed for a new kind of politics to emerge. From the very beginning, groups like ACT UP were highlighting communities that were not being represented in the news. I think that right now complete parts of our society are hidden from the media: homeless population, sex workers, displaced communities. We are only seeing snippets of what is happening in refugee camps in comparison to what is happening at Mt. Sinai hospital or Times Square in New York or the residents of big cities in China and across Europe.

AB: We clearly see a flattening of the representation of the lockdown onto the white and middle-class, urban-dwelling, heterosexual household. Almost all of the governmental and media representation, which at least in Italy are going very much hand in hand, are focusing on this particular category of people. Theirs are the only problems being discussed.

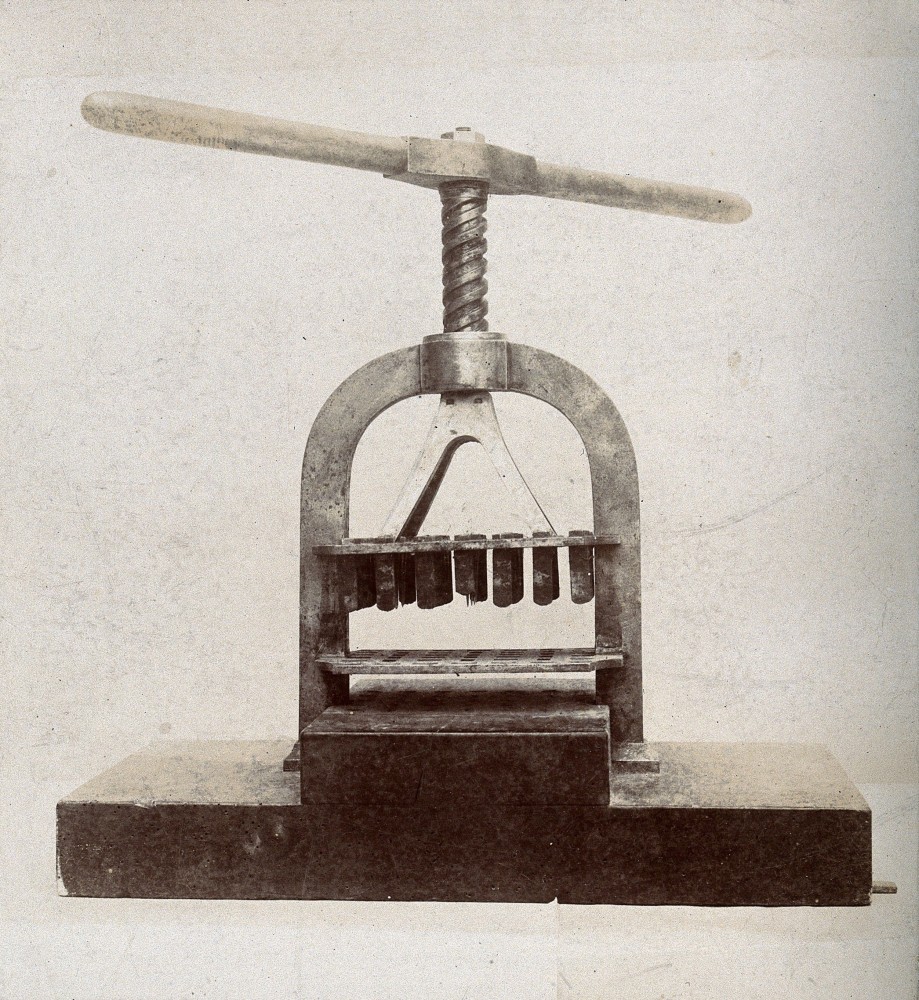

This apparatus, found in the Venice lazzaretto, was used to disinfect letters in times of plague. Courtesy Wellcome Library

As the epidemic has progressed, militarized and racialized language has developed to ghettoize certain groups, specifically Asians. Now as we speak, borders are more or less closed off to people and any kind of human contact is of suspicion, yet products are travelling more freely.

AB: The initial response of almost all political leaders was essentially to downplay the extent of the disease, until it was no longer possible. This temptation to minimize the threat, I think, really has to do with the idea that infectious diseases, and especially epidemics, are perceived as something that does not belong to us. By “us,” I mean the normative Western subject. This of course is something that has a long history and goes back to early modernity or even the late Middle Ages, when the Black Death was characterized as coming from Asia. So there was already a mechanism of othering in place, that continues to define the conception of epidemics in the Western mind. It is the belief that disease is only going to impact those “other” peoples and subjectivities.

Considering this history of othering and dissociation of Western responsibility from the development and transmission of disease, do you see this moment as an end to Western modernity or leadership on an international stage? After an initial lapse in action, China’s now sending doctors and PPE to other countries. The rapid response of its neighbors like Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam has been hailed as exemplary.

AB: I think it's hard to make a claim as to what kind of political landscape we will see on a global scale in six months from now. But it’s helpful to keep in mind that, in many ways, global health is a Western project, and a specifically American project. The WHO, founded in 1948, evolved out of the activities of the Rockefeller Foundation. In a way, this was the first organization to act globally in the field of public health. Of course, this was tied to a precise geopolitical agenda of biomedical expertise as a tool for hegemony. So I think the point is not to think about global health as something that exists outside of politics.

ILM: I would say that this has not been global, even though it has happened all around the world. We have to see that there is an uneven balance of power within different nations and even within the United States. For example, there is no standardized solution as to how masks are used and distributed, and it is often left up to the choice of specific medical institutions. As Andrea was saying, these kinds of global institutions are also carving within themselves certain kinds of politics and ideologies. In most countries, there aren’t centralized forms of health organizations. Even in the United States with the CDC, some of their policies are contradicting their medical data. For example, men who have sex with other men are still banned from donating blood, even though medical knowledge suggests this is unnecessary. This again comes from the legacy of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. We can discuss the role of the expert, but even if we accept the medicalization of the discussion, this ban is just ideological, not medical.

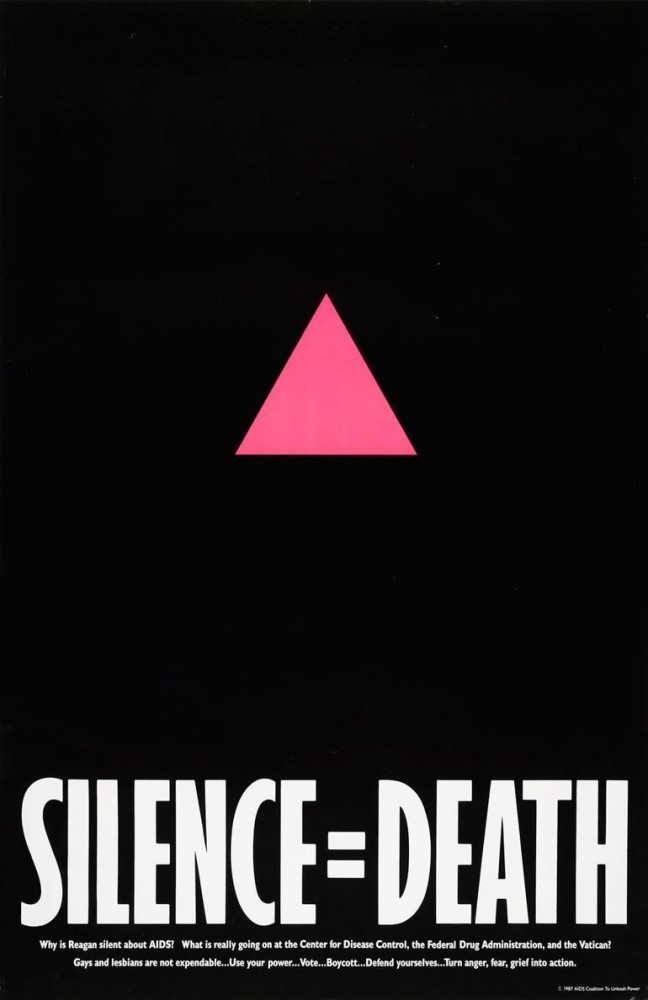

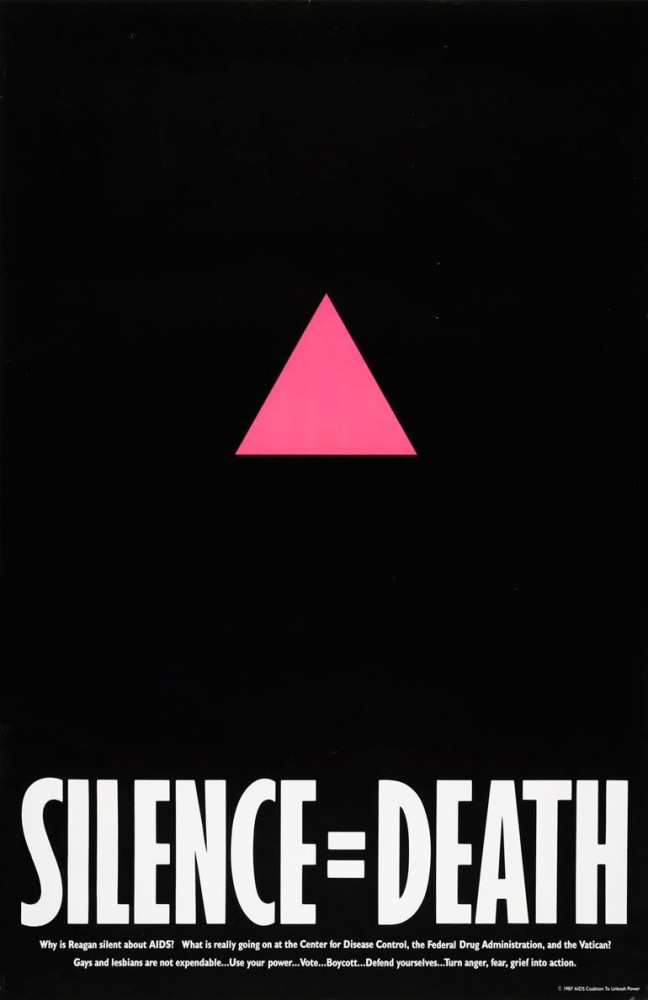

In 1986, Avram Finkelstein was co-founder of the group Silence=Death Project, which created the “Silence=Death” anti-AIDS logo to combat institutional silence surrounding homophobia and HIV/AIDS, later donated to ACT UP. Courtesy ACTUP/Avram Finkelstein

It is important to address how environmental violence has actually increased the situations where outbreaks of epidemics can happen. In China, the issue is not really with wet markets or traditions of specific animal consumption (most of the news coverage were actually highly xenophobic in their descriptions of this), but rather the certain kinds of processes, such as deforestation, urbanization, and destruction of habitats that allows for interspecies jumps of disease to occur. This is not only happening in China, but rather all around the world. In research that Andrea and I are doing together, we are looking at the histories of urbanization in the US and the UK and the rise of Lyme disease as a product of that.

Rainforest juxtaposed with rows of cut trees from the clearance of forest in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Deforestation allows for interspecies jumps of disease to occur. Image courtesy Greenpeace

It’s interesting to think how epidemics are in part instigated by very specific forms of non-urban land management, including the division of plots for resource extraction and organized housing structures for workers. If environmental violence has played a key role in the rise and acceleration of the COVID-19 pandemic, then what urban planning and architectural solutions can we propose that don’t include a “return to nature?” Can we mediate our relationship with the “countryside” without reinstating anti-urban tropes or recreating histories of urban exodus?

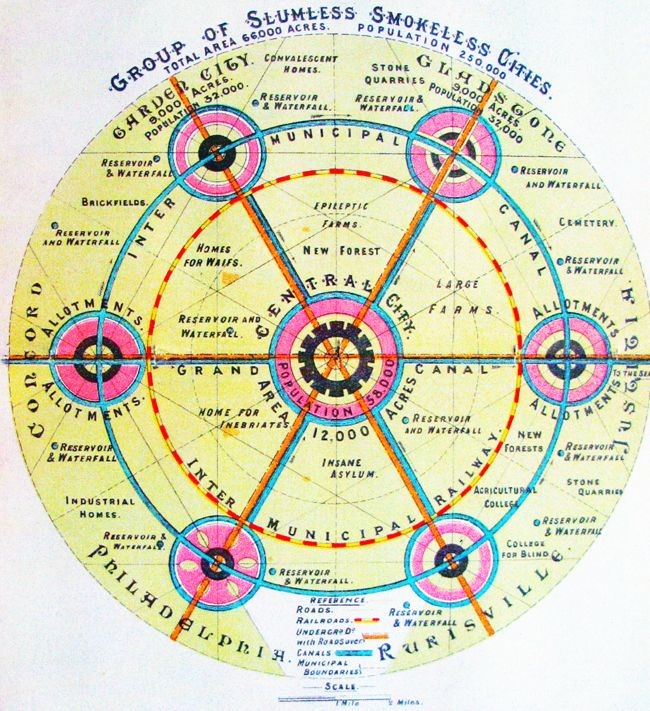

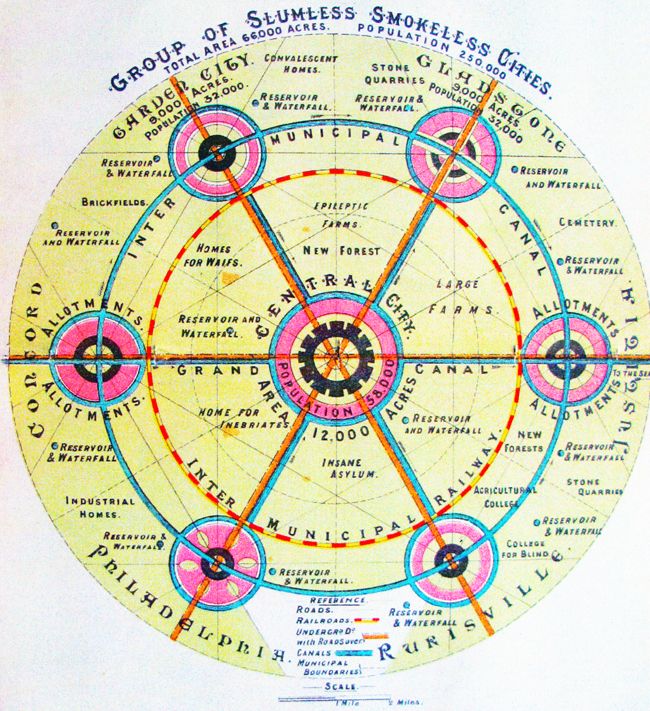

AB: The anti-urban arguments emerging now were already used at the beginning of the 20th century, and are precisely the same arguments that gave rise to the suburbs as we know them. A well-known prototype of the suburbs, the Garden City, was developed out of concern for the city being an infectious landscape — a dangerous place that could corrupt the body as well as the mind. I think architecture needs to be very aware of that history. The point is not that there is a “countryside” and we forgot about it, rather, there is no such thing as a division between the city and the countryside in the first place. Architecture must look critically at cities in their extended scale: urban life doesn’t stop at the city’s limits; it transforms and exploits all species that live in what we call the wilderness.

Ideal city layout from Ebenezer Howard’s book To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Reform (London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co. Ltd., 1898).

And, if we really want to think architecturally about this epidemic, we need to think critically about urban history. Why did Chinese cities industrialize so quickly? Why did so many people move from the countryside to the city? Again, this is a political question, not something that can only be thought of in terms of a natural transformation or as inevitable. In the second part of the 20th century, there was a global urban shift that is still happening. What was the global political vision that pushed people to stop working the land and work in factories, especially in what are now developing countries? Such decisions had huge ecological costs and consequences that we are only now starting to see more clearly. Our point is really that, whatever we want architecture to do, we must be mindful of this history, which is also a history of struggle. It was a struggle for people to leave collective forms of life and kinship to become part of an urban working class.

And sometimes even forced struggle.

AB: Exactly, things were lost. These frictions need to be taken into account.

Chinese construction laborers from the countryside who've migrated to Guangzhou for economic opportunity. Urbanization impacts the transmission and evolution of infectious diseases. Photography by Aaron Reiss

ILM: We also can’t naively consider the countryside as an idyllic green space. The countryside is also the place of fracking, of mineral extraction, and it is also a highly regulated space. If you now consider it as a place for isolation, in this pseudo-way of understanding the countryside à la Walden, then even in New York there is a countryside — Manhattan. While Manhattan is more dense than Queens or The Bronx, there are less COVID-19 cases. Manhattan is also the wealthiest borough and many residents can work from home. So this idea of Philip Johnson’s Glass House and the need to isolate (even from nature) to be productive is actually managing the New York landscape in a certain way. Especially in places like Hudson Yards, where there is a hideaway within the city. I think that we need to get rid of the idea of the countryside as a place of happiness, as it is rather going to be more like Midsommar in its violence. It is a site of exclusion, of segregation.

But we also have to be very wary of the idea that coronavirus is regulating any kind of relationship with the earth. I think it’s extremely dangerous. The famous tweets of dolphins swimming in the Venice canals (which have since been proven to not have taken place) are met with images of disposable masks covering Hong Kong beaches. This moment of being confined in our homes does not allow nature to repair itself, so much as show us that the capitalist productive system is still very much based on the consumption of certain resources.

Nurses protest coronavirus mask and glove shortage outside Jacobi Medical Center in the Bronx, New York. Photography by J.C. Rice.

If anything, this moment has punctured our culture of invisibility. We are forced to confront a network of workers, many of whom are immigrants and women of color, who are generally unprotected, underpaid, and have largely gone unseen until now. They work in factories alongside automated robotic-colleagues, in grocery stores, making deliveries, and on the front-lines of the COVID-19 hospital response as nurses and maintenance workers. In the context of New York, many of these workers live in the outer boroughs, which are poorly connected to each other by public transportation but all connect directly to Manhattan.

AB: Here in Italy, the epicenter of the epidemic has not been in the city proper but rather in the hinterland of Milan. It is not quite suburban, as it has a lot of factories and small and medium enterprises. It is a peculiar landscape — it’s very urbanized, but in a kind of diffused way where people move a lot between different centers.It’s one of the most polluted areas, not just in Italy, but in the world. For so long these areas North and East of Milan have been erased from national consciousness. We all knew that it was a productive region, but the way people actually lived there was not at all part of the representation of Italy as a “beautiful country.” Precisely as you are saying, Samantha, we are now seeing these geographies forcefully coming to the fore: it was the economic imperative not to stop production that led contagion to expand as quickly as it did.

If we consider microbes as part of the environment, what does that mean for discussions of urbanization? And in this context specifically, can we create a positive relationship with the viral microbes that many humans have been forced into an interspecies relationship with? Within this, is there a potential to de-center the idea of the human from this discussion?

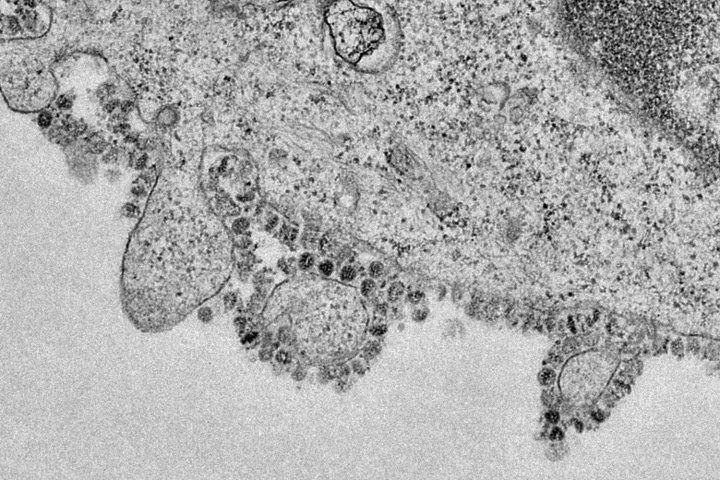

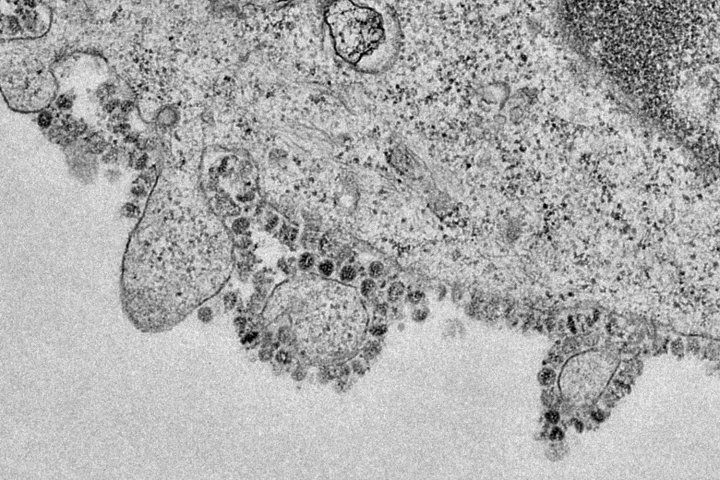

An electron microscope image showing particles of the new coronavirus being released from an infected cell. Image courtesy the University of Hong Kong

AB: The question of coexistence is central to all our work. It’s delusional to think that we can exclude microbes from our bodies and from our society. I think this goes back to the question of the way that coexistence has been experienced historically by those communities and groups that were outside of, let’s say, Western modernity. Modern science does have a way of dealing with microbes, especially when they are dangerous, and even articulate and sophisticated, but it is not the only way. In my research into malaria in Italy in the 19th century, I realized how peasants in the South were coexisting with disease and insects. While we shouldn’t draw any direct comparisons with today, it’s important to note that people at that time had strategies for living and thriving in a pathogenic environment. For example, they developed a rhythm for working the fields and managing the wetlands that minimized their exposure to contagion — long before malaria was understood as a medical problem.

ILM: The discovery of the human genome showed us that our bodies have more bacterial cells than human. However, we now have to redefine what a healthy body is. As the conversation shifts to the importance of testing for antibodies, it brings up issues for immunosuppressive people and other individuals. This could even change the definition of citizenship. It’s something that is very active in the conversation right now surrounding those living with HIV/AIDS. Even with access to PrEP and Truvada HIV/AIDS is not something from the past. There are many different definitions of what a healthy body is, or even what a body is. We have to find ways of coexisting with “unhealthy” bodies, with disease, and with epidemics. Otherwise, we are actually defining different levels of citizenship and the right to be a citizen.

If we continue to understand architecture as isolated buildings we are going to fail. Architecture is a relational discipline, as well as an activity and action. If we are talking about a response to an epidemic, we have to take into account the many different doctrines that are intervening in this piece of architecture to produce a response that could be effective. It is not only about the construction in a specific place or a space itself, but the relationship with wider geographies — how resources are extracted, what the relationship is with other urban or rural areas, what economic, political, and ideological systems are at play, and, how this architecture caters to other communities.

Interview by Samantha Ozer.

Images courtesy the author, Andrea Bagnato, and Ivan L. Munuera.