HOUSE PARTY: Alex da Corte Deconstructs the American Media Psyche in Shanghai

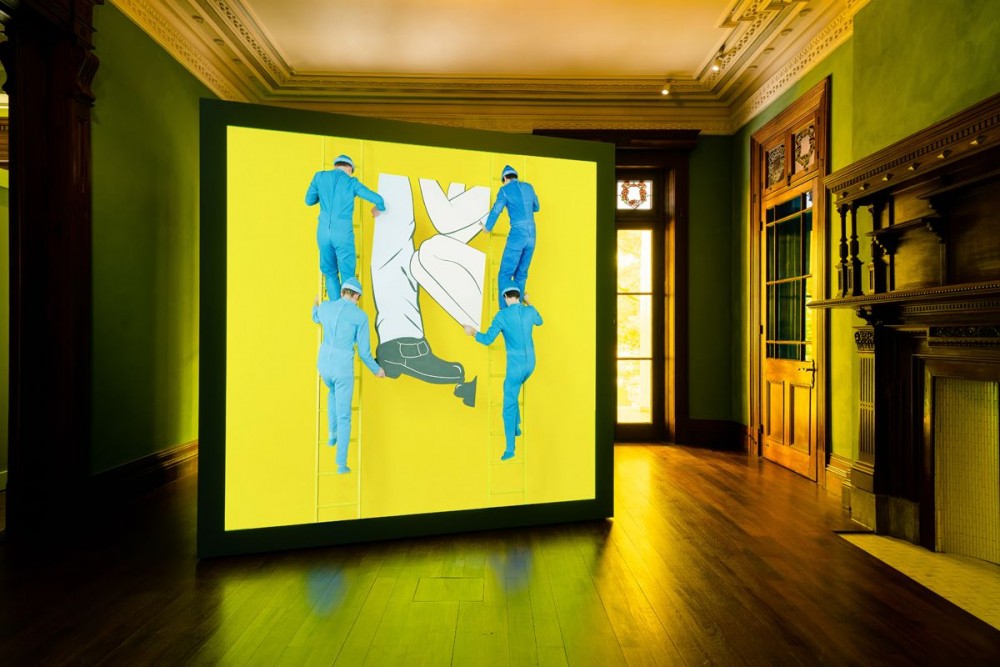

Alex Da Corte’s Rubber Pencil Devil at Prada Rong Zhai. (Photo by Alessandro Wang. Courtesy Prada.)

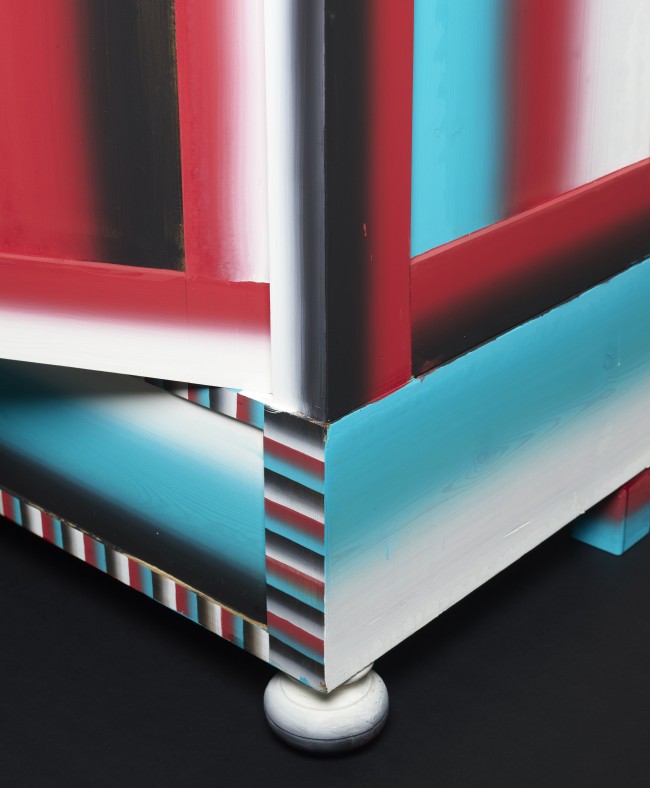

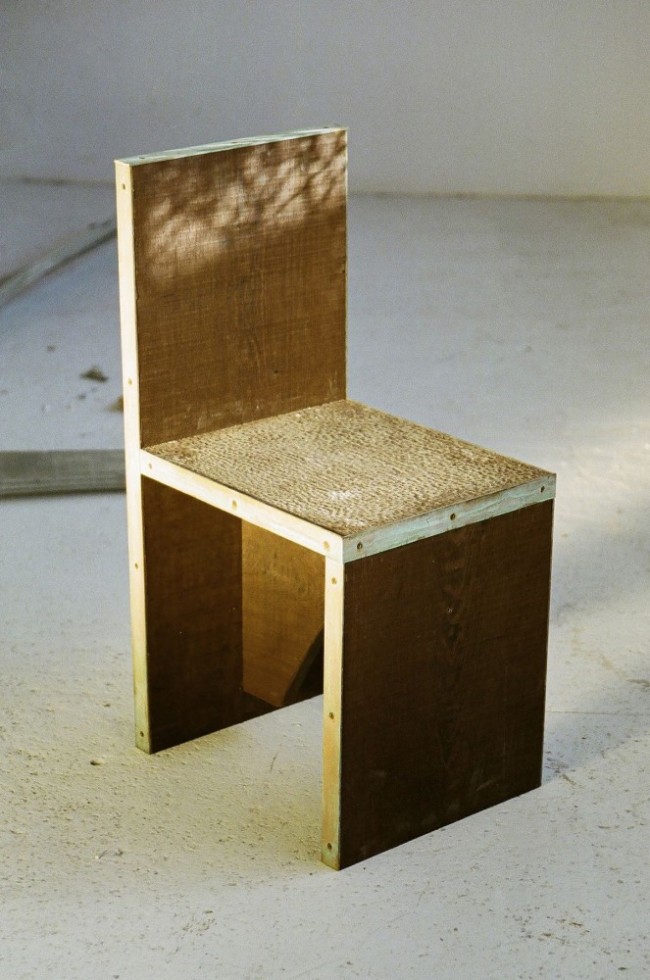

Alex Da Corte’s Rubber Pencil Devil, now on view Prada Rong Zhai, is pure spatial chaos — and that’s precisely the point. What was once a single-channel 180-minute video is now distributed across 20 sculptural cubes,

Alex Da Corte’s Rubber Pencil Devil at Prada Rong Zhai. (Photo by Alessandro Wang. Courtesy Prada.)

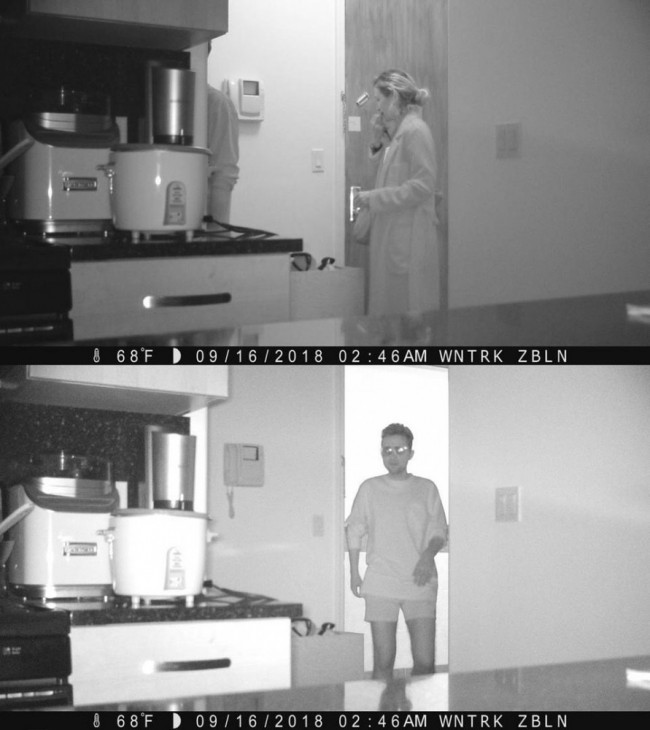

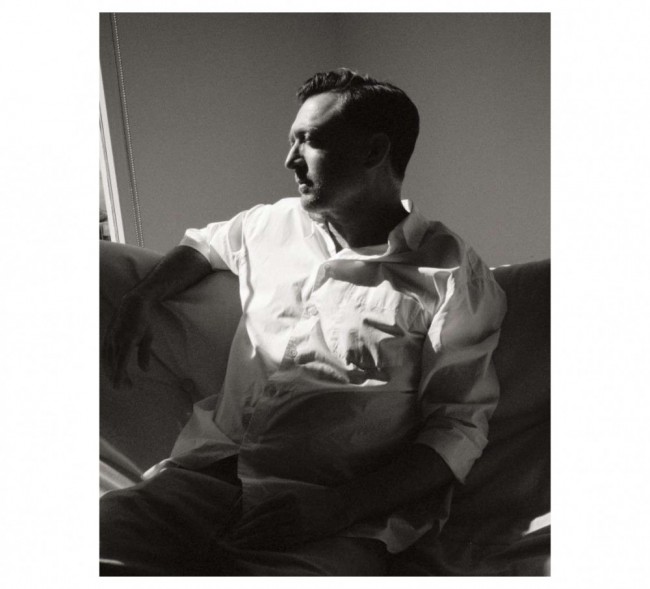

Rubber Pencil Devil, first exhibited in 2018, shows Da Corte and a handful of assistants giddily embodying more than 50 pop-cultural icons, including Mister Rogers, Popeye, Bugs Bunny, and the devil himself. Da Corte plays the majority of these facsimilar figures, though is often unrecognizable under full-body suits and prosthetics, communing with animated bluebirds or dancing like Fred Astaire in front of bright-colored seamless. Da Corte’s work is known for its meticulous synthesis of the real and the unreal, and the show at Rong Zhai is no exception: it seeks to destabilize the viewing habits one deploys, perhaps without even thinking, on a daily basis. The broader context of the global pandemic intensifies this uneasiness. “‘Where does one sit at a disaster?’” Da Corte asks in an interview with Fondazione Prada curators Mario Mainetti and Carlo Barbatti, quoting the critic Norman Klein, noting that he finds the question especially helpful for thinking through his work as a “moment of viewing a chaotic sensorial video in a public space.” Rubber Pencil Devil at the Rong Zhai isn’t happening in the midst of a disaster; it’s the disaster itself.

This is not the first time Da Corte has schemed to both orient and disorient the viewer. In 2010, he mounted simultaneous shows, The Island Beautiful and Mortal Mirror, in adjacent, gentrifying Philadelphia neighborhoods. Presented in identical formats at same-sized galleries, the discordant imagery at each show — a stuffed cat mummified in Saran Wrap, a lozenge stuck to Stevie Nicks’s cardboard heel — competed for the wandering viewer’s psychic real estate. Recalling the dual event, Da Corte says, “I proposed that the viewer, when experiencing either show, navigate the lingering effect of the other in (their) mind…It is often my aim to present a play of feelings that require the viewer as vessel.”

Alex Da Corte’s Rubber Pencil Devil at Prada Rong Zhai. (Photo by Alessandro Wang. Courtesy Prada.)

As Da Corte’s art-star has risen, the audiences and venues at the center of this exercise have evolved. Still, to him, the same potential to engage with the viewer remains: “I think Rubber Pencil Devil in Rong Zhai is (another) example of this kind of sensorial contamination,” he explains, referring to

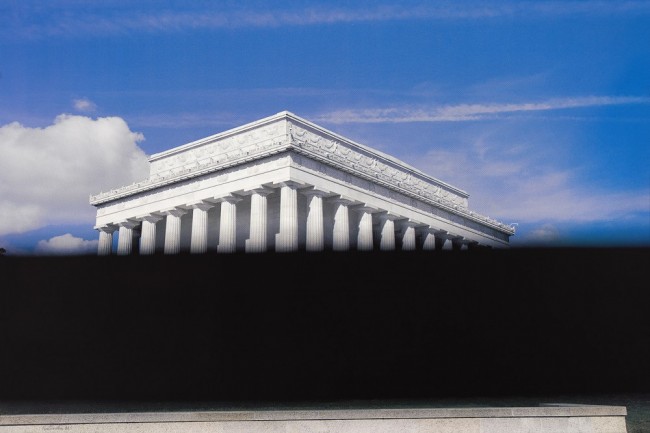

The Prada Rong Zhai serves as a built-out proxy for what has become a scenographic motif of Da Corte’s: neon. As Annie Godfrey Larmon writes in the artist’s 2016 monograph Free Roses, the ambient neon light cast by his installations both envelops and unmoors the viewer: “The glow is a dominating force in his immersive installations — it renders everything cinematic, infusing the space with potential as it severs a viewer’s coordinates from the world beyond the neon.” Case in point: When Da Corte debuted Devil in Pittsburgh, at the 57th Carnegie International, he enshrined the video in the skeletal light-up frame of a typical single-story home, displaced from an imaginary suburban street to the interior of the Carnegie Museum. In a sense, the 1918 mansion now known as Prada Rong Zhai is just as anomalous to its surroundings. Nestled in central Shanghai, in the French Concession neighborhood, Rong Zhai stands out from its urban environs by design. The product of both local and imported architectural traditions, the house amounts to a kind of cultural Rorschach: one guest may perceive its imperial archways as Shanghainese, while others may see a European court in its parquet floors. Da Corte’s reprisals of dispossessed Americana are no more or less “at home” in the space than the house itself is in East Asia. If Da Corte’s neons prime the viewer for psychosocial contamination, so does the venue in which Devil is currently housed.

Alex Da Corte’s Rubber Pencil Devil at Prada Rong Zhai. (Photo by Alessandro Wang. Courtesy Prada.)

Following a year of cancelled openings and sign-up only masked museum visits, the festive opening of Da Corte’s Rubber Pencil Devil at Prada Rong Zhai this November appeared as a kind of ghost of an art world past for those of us in countries that haven’t yet bounced back from Covid: The usual mix of artists, gallery directors, and models huddled together for photo ops, playing in the field of exhibitionism and consumption that Da Corte’s work itself has long refracted. Da Corte came up at the dawn of the web 2.0 era, as post-Recession, DIY hedonism was descending upon the greater New York art and nightlife scenes. A circumscribed industry formed around artists like Da Corte,

The hardly new collusion of global art and fashion is but a pure extension of this peculiar feedback loop between libidinal desire, contemporary media, consumer culture, and social scene. Da Corte addresses this slippery in- and out-grouping in the conversation printed in the Shanghai show’s catalogue: “Play has always been a way for me to carve out a magic circle for my work…(and) there was initially a critique of this kind of process,” he says. “I had a Brechtian tendency to alienate the viewer if they were not clued into the idiosyncrasies of the circle.”

Alex Da Corte’s Rubber Pencil Devil at Prada Rong Zhai. (Photo by Alessandro Wang. Courtesy Prada.)

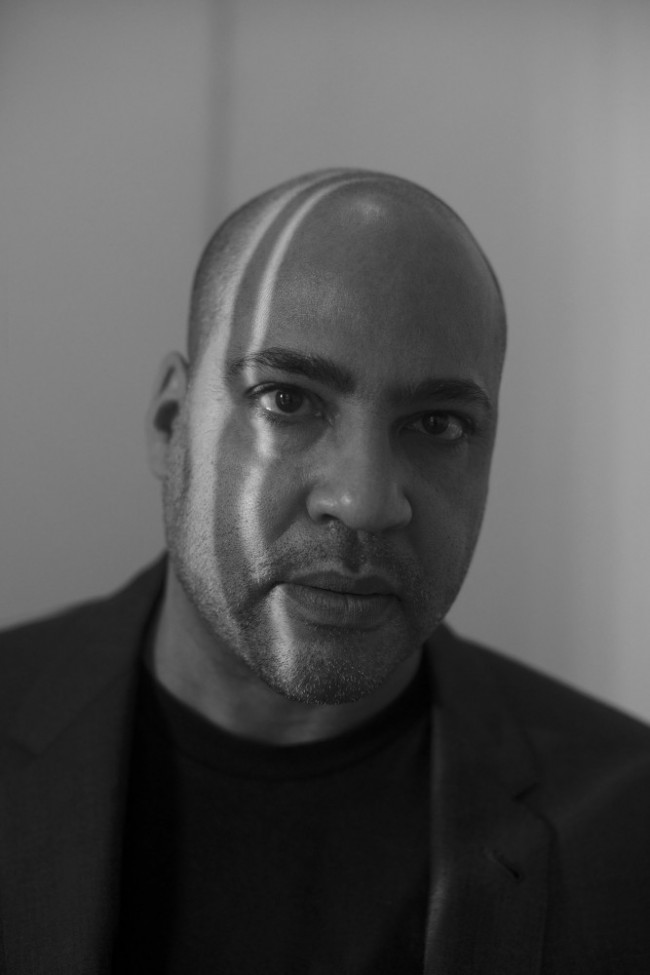

But, in truth, the artist has long cultivated his “magic circle” outside the creative-industrial center. Raised between New Jersey and Caracas, he’s now a diehard Philadelphian, housing his studio in a converted candy factory. Of his multifaceted oeuvre, Rubber Pencil Devil in particular incorporates the fabric of Da Corte’s adoptive rustbelt home: “(The piece) was developed...while ruminating on Pittsburgh(’s) post-industrial city’s output—specifically Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and Heinz Tomato Ketchup,” Da Corte tells Fondazione Prada, adding that the number of chapters is a direct reference to Heinz’s “57 Pickle Varieties.”

It’s this post-industrial, pre-online epoch that is evoked in Devil — one more shaped by the dissolution of the American Dream than that of the mid-aughts New York party circuit. But a sense of play is still integral to Rubber Pencil Devil’s media landscape, where the television phantasmagoria is periodically interrupted by slapstick, as when Da Corte-as-Mr. Rogers slips and falls on his ass. The scoring, with tracks like LeAnn Rimes’s “Blue” and Dolly Parton’s “Light of A Clear Blue Morning,” verges on schlock. In their temporary home in Shanghai, these dramaturgical bonbons are all the more spectral and alluring. The American dream may be dead, but we can still have a little fun.

Text by Samuel Anderson

All images by Alessandro Wang and courtesy Fondazione Prada

Rubber Pencil Devil is on view at Prada Rong Zhai, Shanghai until January 17, 2021.