ABRAXAS: The Somber Beauty of Ricardo Bofill’s Parisian Social Housing Vision

abraxas, abrasax, abracadabra. a Gnostic mystery and probable mistransliteration that has fascinated for two millennia. That which is spoken by God-the-Sun is life; that which is spoken by the Devil is death; abraxas speaketh that hallowed and accursed word which is life and death at the same time. abraxas begetteth truth and lying, good and evil, light and darkness in the same word and in the same act. Wherefore is abraxas terrible.

— From the third of Carl Jung’s Seven Sermons to the Dead (1916)

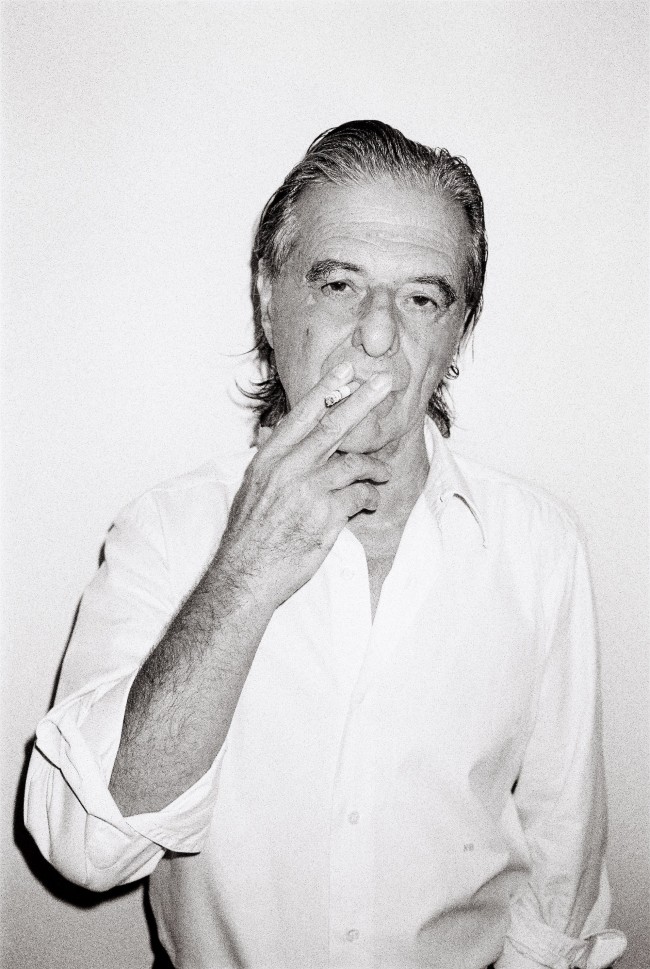

“Les Espaces d’abraxas” (literally “abraxas’s spaces”) is the name architect Ricardo Bofill gave to the 600-dwelling social housing project he and his Taller de Arquitectura built at Noisy-le-Grand, less than 8 miles east of Paris, in 1978–83. It was one of several such projects realized by Bofill in France, all of which he intended as alternatives to the Modernist grands ensembles that had dominated public-sector housing production in France’s postwar era.

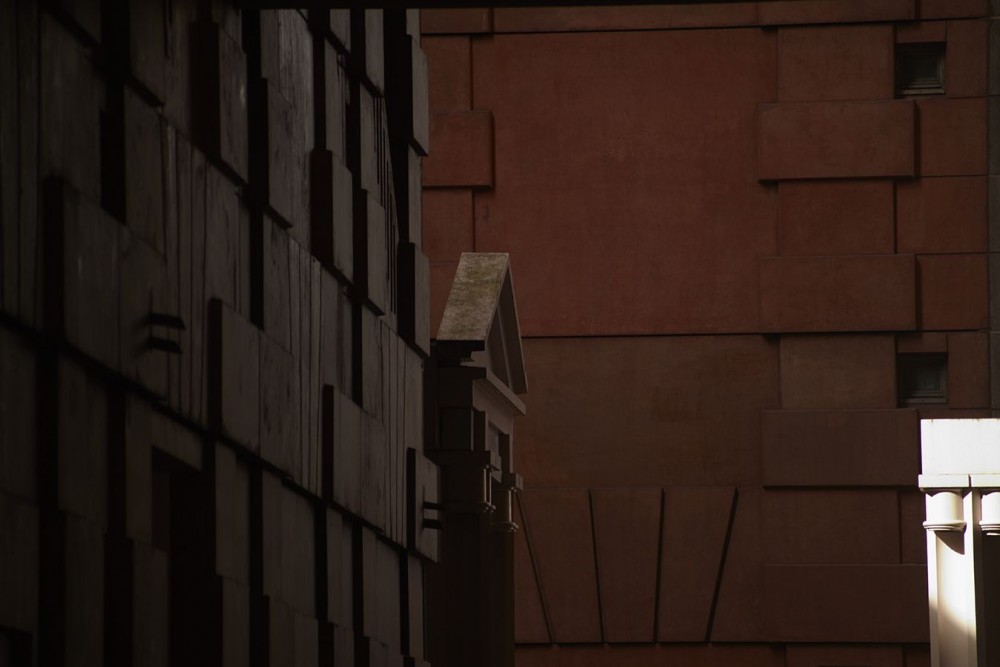

Abraxas public housing complex, Noisy-le-Grand, near Paris (1978–83). Designed by Ricardo Bofill, Taller de Arquitectura. Photographed by Devin Blair for PIN–UP.

To counter what was perceived as the soullessness and lack of identity that reigned at the grands ensembles — which mostly took the form of utilitarian slabs and towers set among grass and parking — Bofill abandoned their concern for rational organization around sunlight and vehicular access in favor of high-density monumental “Baroque” planning dressed up in columns, predicaments, and entablatures. Realized at an industrial scale, his Neoclassical housing projects were built using standardized high-quality prefabricated-concrete elements developed in partnership with construction companies.

Abraxas public housing complex, Noisy-le-Grand, near Paris (1978–83). Designed by Ricardo Bofill, Taller de Arquitectura. Photographed by Devin Blair for PIN–UP.

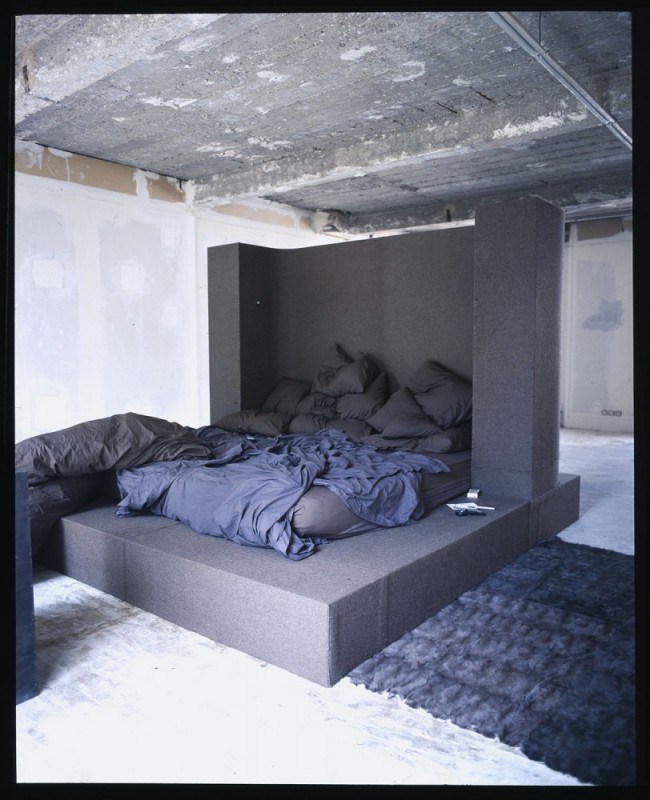

Commissioned by a Communist municipality, Abraxas was conceived as a “Versailles for the people” — as Bofill memorably described an earlier scheme at St.-Quentin-en-Yvelines. Three edifices make up the Abraxas project: the cliff-like 19-story Palacio, the semi-circular ten-story Teatro, and, enclosed at the center of the space formed by these two mastodons, the slightly more modest Arco. An obvious descendant of grandiose Classicizing Eastern-bloc schemes like Moscow’s Seven Sisters or Berlin’s Stalin- (now Karl-Marx-) allee, Abraxas nonetheless differentiates itself by eschewing their discredited Social Realism in favor of a troubling mantle of Surrealism. Here it is the silent, empty, melancholy spaces of Giorgio de Chirico that are embodied in a self-reflexive seeing machine, a claustrophobic auto-policing Panopticon where a thousand blank eyes stare down you in dumb surveillance.

Abraxas public housing complex, Noisy-le-Grand, near Paris (1978–83). Designed by Ricardo Bofill, Taller de Arquitectura. Photographed by Devin Blair for PIN–UP.

In Abraxas, the inflation of scale often renders form and content out of synch — columns turn out to be staircase towers or living-room windows, while entire apartments shelter in a two-story Doric frieze. Supremely photogenic, like much totalitarian spectacle, Abraxas stood in for the FBI headquarters in Mais qui a tué Pamela Rose? (2003), and for dystopia in general in Brazil (1984). Or as Bofill himself said about an earlier Maison d’Abraxas he planned but never built at St.-Quentin, “The staircase will stop at a platform from which one could listen to music by Wagner... or commit suicide if one so desired.”