Photo by Daniel Salemi. Courtesy of Miu Miu.

Photo by Daniel Salemi. Courtesy of Miu Miu.

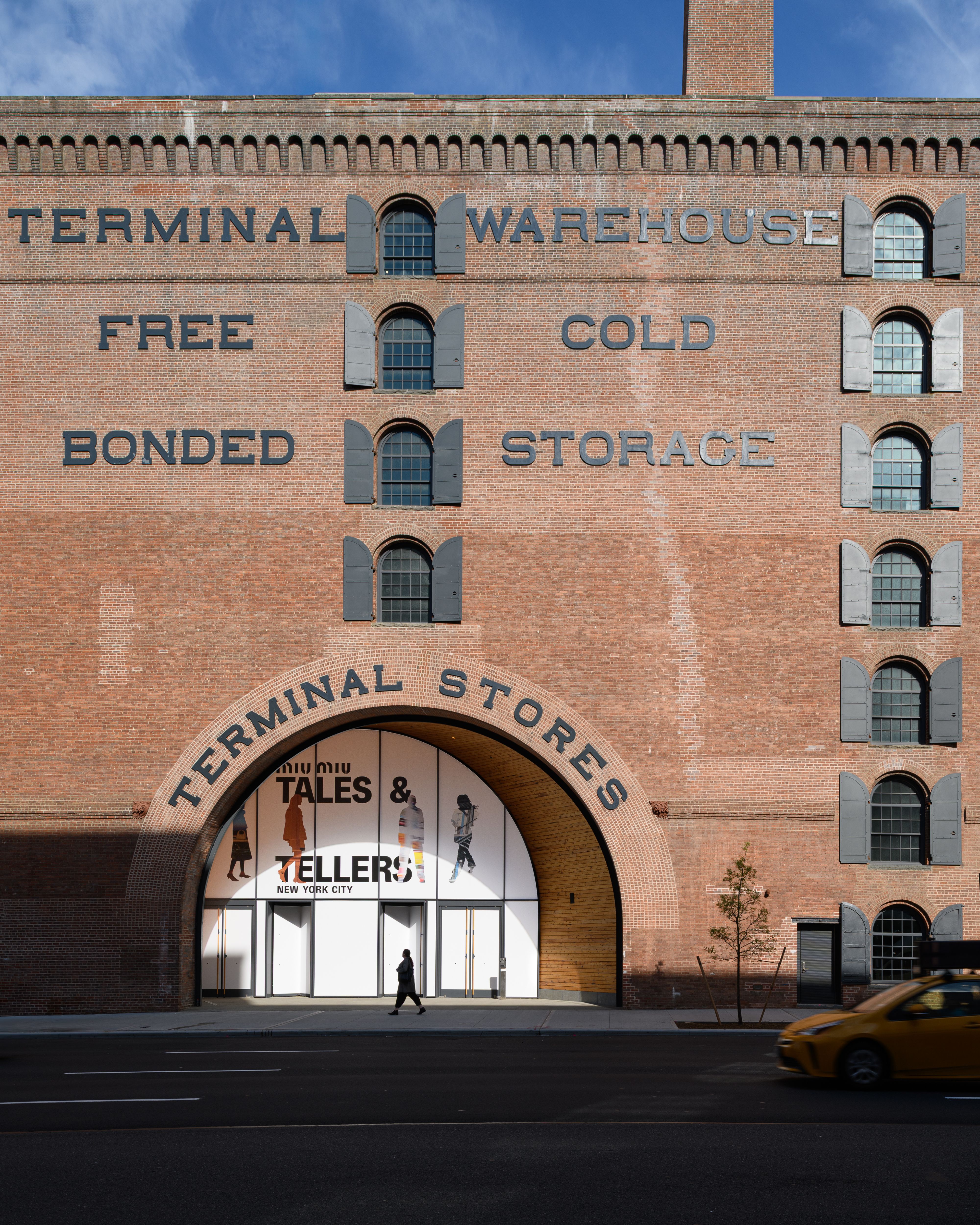

A stand-up comedian, a construction worker, and an opera singer walk into a former nightclub. It sounds like the set-up for a joke, but it was one of the many scenarios that played out in New York in early May at the second iteration of Miu Miu’s Tales & Tellers. The immersive activation, conceived by interdisciplinary artist Goshka Macuga and organized by curator Elvira Dyangani Ose with choreography by theater and opera director Fabio Cherstich, took Miu Miu’s Women’s Tales series — a program of 35 female-directed short films that began in 2011 — as its starting point. Macuga and Ose extracted the lead characters from each one and brought them to life in a highly choreographed yet spontaneous performance, grounded by scenography from OMA, and staged in the cavernous space that once housed legendary club The Tunnel in Chelsea. The aforementioned comedian, for example, is Carmen, a woman with a dry sense of humor, pulled from a short directed by Chloë Sevigny. The construction worker is Stane, who is about to inherit her Croatian immigrant father’s construction business, from a film directed by Antoneta Alamat Kusijanović. And the opera singer is Luz, a woman who works at an art gallery but whose true calling is classical music, from a vignette directed by Lila Avilés.

The first iteration of Tales & Tellers took place in October 2024 during Art Basel Paris at the Palais d’Iéna, architect Auguste Perret’s 1937 reinforced concrete masterpiece and the space where Miu Miu has been staging its runway shows since 2011. There, performers moved through the grand, colonnaded hall like living sculptures, reanimating characters from the Women’s Tales films in a slow, deliberate choreography that mirrored the building’s formal character. To complement the performances, Miu Miu also hosted a series of talks with various creatives from the long-running film series, including Meriem Bennani, Chloë Sevigny, Hailey Gates, Shuang Li, Zoe R. Cassavetes, and Haifaa Al-Mansour. The Paris exhibition was slightly smaller in scale than the New York iteration, but both were designed to explore the concept of public space. Of course, public space in Paris carries a vastly different cultural meaning than in New York — think Haussmannian boulevards and the open expanses of the Place de la Concorde, Place de la République, or Place de la Bastille, which are not just everyday gathering places but also historic stages for protest and public dissent. The light-filled Palais, then, cast different shadows on the performances compared to the narrow darkness of a former Chelsea railroad freight terminal.

Photo by Daniel Salemi. Courtesy of Miu Miu.

Photo by Daniel Salemi. Courtesy of Miu Miu.

Photo by Daniel Salemi. Courtesy of Miu Miu.

Photo by Daniel Salemi. Courtesy of Miu Miu.

At the New York iteration of the project, the actors — or “custodians” of the tales, as Macuga and Ose called them — roamed the space, all dressed in the Miu Miu collections featured in the films, many of which were archival pieces. They moved in a frenzied manner to mimic the energy of a busy New York City street. When I first walked into the space, one actor was working at a computer, sitting at a curved reception desk flanked by two coffee cups — a bureaucratic intervention that reminded me of Adrian Piper’s The Probable Trust Registry. Nearby, a character in bedazzled hot pants practiced her jabs and uppercuts before wrestling with the actor next to her. A woman who I initially thought was just slumped against the wall looking at her phone approached me and showed me her screen, which was playing one of the Women’s Tales. A couple of times, techno music blared, and all the characters gathered in the middle of the room to dance — a reference to the space’s storied nightlife past. “I never really approach my work as a blank canvas. I always try to address the context and history of the space,” Macuga explains amidst the controlled chaos of the performance, just before a fleet of actors sits behind us on the central seating structure, flipping up newspapers in a particularly camera-ready moment.

Macuga faced a near-impossible task: creating something new and cohesive from an archive of films made by dozens of artists over 14 years, all staged in one dark, cavernous space. She didn’t want to just show the films in a classic sense, although there was a “cinema” off the main space where they were screened. Instead, she opted to pursue the equivalent of an archaeological dig on the materials — a process of “breaking the frames, like in a dream,” as her collaborator Cherstich described it. “You let the character be alive. You break the frame of the exhibition because it’s not an exhibition. You break the frame of the theater because we’re not in the theater,” Cherstich adds. “There’s a burden of a statement or a signature artwork, or a set idea of how you work, and I always like to reinvent my approach to artmaking,” Macuga tells me. “Here, if I were to describe my role, it was much more curatorial than artistic because the ingredients are not my creation. I just put them together in a different way.” Although many people I spoke with didn’t fully grasp the premise, it didn’t seem to matter — the theatrics still landed. Where most brands might stumble with something this layered and ambiguous, Miu Miu made it work.

Photo by Daniel Salemi. Courtesy of Miu Miu.

Photo by Daniel Salemi. Courtesy of Miu Miu.

Terminal Warehouse — the former Tunnel nightclub in a historic rail terminal — hosted the New York edition of Tales & Tellers. Photo by Daniel Salemi. Courtesy of Miu Miu.

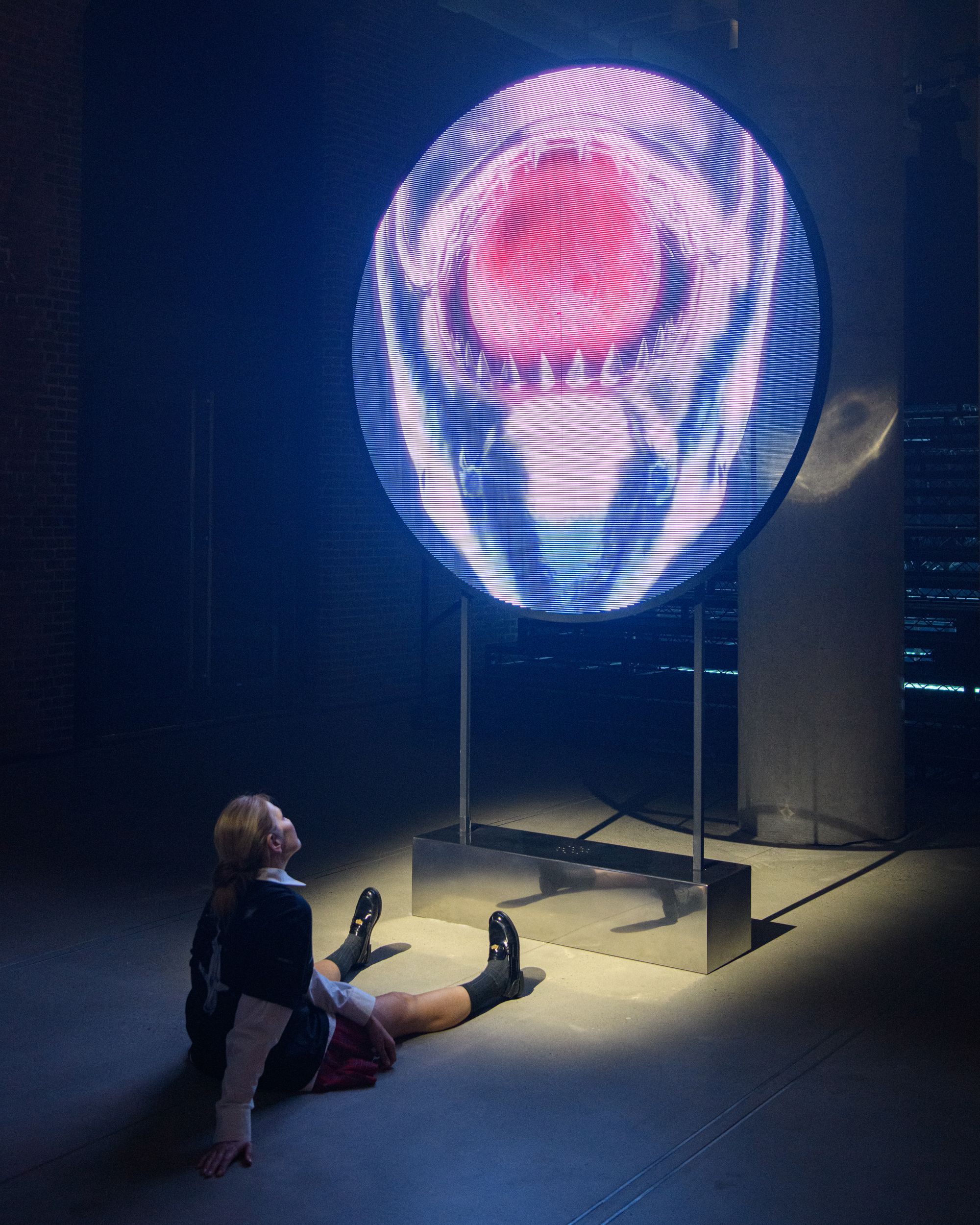

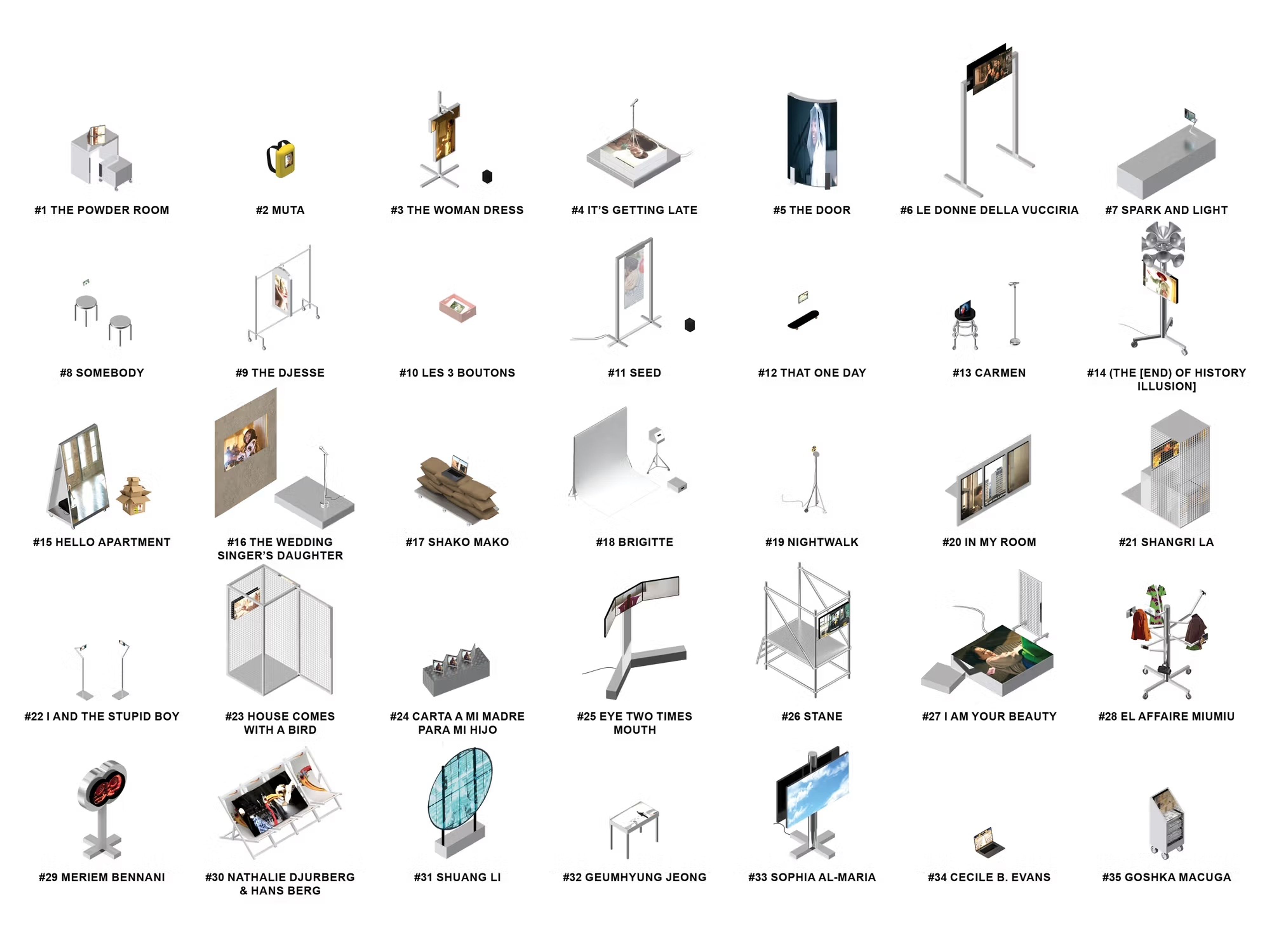

The performers were grounded by scenography by OMA, who have collaborated with Prada on fashion shows for years. Each Tale was screened on a different chrome-finished object-cum-screen, ranging from a binocular-shaped platform to a vanity with a screen built into the mirror, which each character interacted with. One was even shaped like a cage. As OMA associate Giulio Margheri tells me, these devices or objects are abstractions of each of the films. “Sometimes it’s a specific moment, or something you see in the video, and sometimes it’s purely representing an element.” Each device had a screen embedded within it at different scales— some small enough that you had to get really close to it, while others were large enough that the light from the video reflected elsewhere in the room. The family of objects was essentially the same from the first performance, so it’s interesting to imagine them sitting in a storage space in Milan or Paris, like circus props on hiatus, stuck in limbo between performances.

Beyond the smaller-scale devices, OMA worked on the larger scale of the full space, closing off one end with risers that became a part of the performance itself, and the Lounge, where people could sit, hang out, and read Goshka’s The Truthless Times, a speculative newspaper developed by 2x4 that debuted at the first iteration of Tales & Tellers. According to co-editor India Ennenga, the paper is an “object from a future world,” dated 2034, that plays on “ideas of institutional neutrality and journalistic objectivity.” The Truthless Times features only cryptic headlines— Tourists Reach Terminus at Last Resort, Endings Unending as Future Moves to Past, We’re in the Endcore Now— and QR codes, which take you to a real news story, journal article, or essay if you scan them. From these sometimes knowingly ironic and overly literal headlines comes “a vast world of critical engagement,” says Ennenga, featuring a few special commissions from Shumon Basar, Legacy Russell, and Kate Crawford that touch on everything from the future of AI to polarizing opinions on climate change photography, animal life, and sports.

A grid of the devices OMA made for Tales & Tellers. Courtesy of OMA.

Photo by Daniel Salemi. Courtesy of Miu Miu.

Photo by Daniel Salemi. Courtesy of Miu Miu.

“The newspaper is one piece of the larger whole in Tales & Tellers, but I think it reflects some of Goshka’s core interests that were also played out in the exhibition: the layering of multiple realities and narratives, the blurring of performance, truth, and the performance of truth,” says Ennenga. “I really admire Goshka’s commitment to addressing the gamut of modern human experience — with all of its inherent contradictions and complexities — and how she applies the same intellectual rigor to large political questions as she does to small moments of joy.”

That layering felt especially clear at the end of the evening when one of the most surprising architectural elements of the show was revealed: a big black curtain that hugged the entire wall of one side of the room opened up to a hidden courtyard, where the performers were posed straight ahead, staring at the audience through transparent glass. It was the scene most similar to a traditional fashion presentation that occurred all night. The mannequin-like poses felt tame compared to the energy the performers had been drumming up across the space in the preceding hours.

Worldbuilding around fashion is often an exercise in aspirational aesthetics, but the women in the films — and the ones careening across the warehouse all evening — were sometimes caught in moments of instability, transition, or emotional limbo. Miu Miu’s women are imperfect. You might want to wear their clothes, but you don’t necessarily want to be all of them. I felt this with the Kusijanović-directed Stane — the short about the construction worker, who is emotionally unraveling as her marriage crumbles. In one scene, Stane storms atop a table in a Croatian cultural hall, dancing ecstatically in a butter-yellow prairie dress as her husband tries to pull her down and her peers look mystified. It’s an out-of-control moment that borders on madness. Not the usual fluffy fashion fare. With the actors staring back at us through glass frames, the line between performer and audience blurs even further. In that moment, unified by a common gaze, we all become Miu Miu women.

Photo by Daniel Salemi. Courtesy of Miu Miu.