JONATHAN OLIVARES

AN INTERVIEW ON DESIGN AND SKATEBOARDING, QUOTES, AND THE PLACE OF THE CHAIR

by Felix Burrichter

Jonathan Olivares photographed by Caroline Tompkins for PIN–UP 33.

Jonathan Olivares is something of a designer’s designer. It’s not that his work is inaccessible — you’ve likely seen it, sat on it, or shopped in it without having to give it much thought. In the words of author Leah Whitman-Salkin, Olivares’s interventions “seldom resort to fanfare, privileging use-value and tenderness over showmanship.” Whether in retail spaces like Camper’s Rockefeller Center shop and Blum & Poe’s Los Angeles bookstore, seating at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, workstations for Dropbox Headquarters, exhibitions for Vitra, or Kvadrat’s Park Avenue flagship, Olivares subtly shapes environments through thoughtfully choreographed design. The same consideration goes into individual objects — daybeds, public seating, or, perhaps his favored form, the chair. Such simplicity belies the complex network of techniques, influences, and relationships that help bring it into existence. While most designers rely on a furniture brand’s supply chains, Olivares seeks out architectural metal manufacturers like Zahner, aerospace and nautical suppliers, or industrial stone quarriers, and draws inspiration not only from the history of high design but from architecture and one of his lifelong passions: skateboarding. Olivares is also drawn to publishing, and has authored or edited six books to date, including A Taxonomy of Office Chairs (Phaidon, 2011), Selected Works (powerHouse, 2017), and Seeing (Nieves, 2022). Now at a turning point in his career — he was just appointed the new design director of U.S. furniture giant Knoll — the 41-year-old sat down with PIN–UP to outline his design philosophy and what it specifically means to be an American designer.

For feminist skate collective Brujas, Olivares repurposed theatrical staging equipment to create the indoor, cop-free Training Facility at Performance Space in the East Village, not far from skate spots in Tompkins Square Park and the Lower East Side. From May 25–June 9, 2018, the pink-concrete-accented space hosted open skate sessions as well as workshops. The Brujas project numbers among many collaborations by Olivares, including with Precious Okoyomon for their 2021 project at The Shed.

Felix Burrichter: What was your early design education?

Jonathan Olivares: It was a little bit Choose Your Own Adventure: Boston College for a year, The New School for a year, and then Pratt Institute for three years. So philosophy with Jesuits, literature at the birthplace of the Parsons table, and finally technical training with old-timers who had worked for George Nelson, Walter Dorwin Teague, and Henry Dreyfuss. The attitude at Pratt was “mock it up before you fock it up” — lots of full-scale drafting, welding, and the whole place smelled like Bondo. You could smoke cigarettes in most classes. Those were kind of the things I felt I needed at that age.

What was your thesis project?

I asked too many questions for the undergraduate classes, so the chair moved me into Bruce Hannah’s graduate-thesis class. My title was “The Object of Cinematic Imagery”: I wanted to study objects in use but avoid IDEO-style amateur anthropology, which I don’t believe in as a practice or methodology. I was interested in how the auteur directors used objects, for example Harmony Korine in Gummo, when Mark Gonzales wrestles a chair, deforms it, and transforms its use value entirely. For a year I lived in Kim’s Video, Film Forum, and Pratt’s 16 mm library. I was used to reading 500 pages a week at Boston College and the New School, so when I arrived at Pratt I was like, “What’s the course reading?” But there was none. I think I went to complain to the chair of the department, and she was like, “Well, we have a library.” I worked my way alphabetically through the entire library collection in six months — it was fast because design books don’t have very many words. [Laughs.]

Books are an important part of your practice and there’s a very specific way you work with them. What I find fascinating about your most recent one, Seeing, is that it’s the smallest and shortest you’ve done, but also the most revealing.

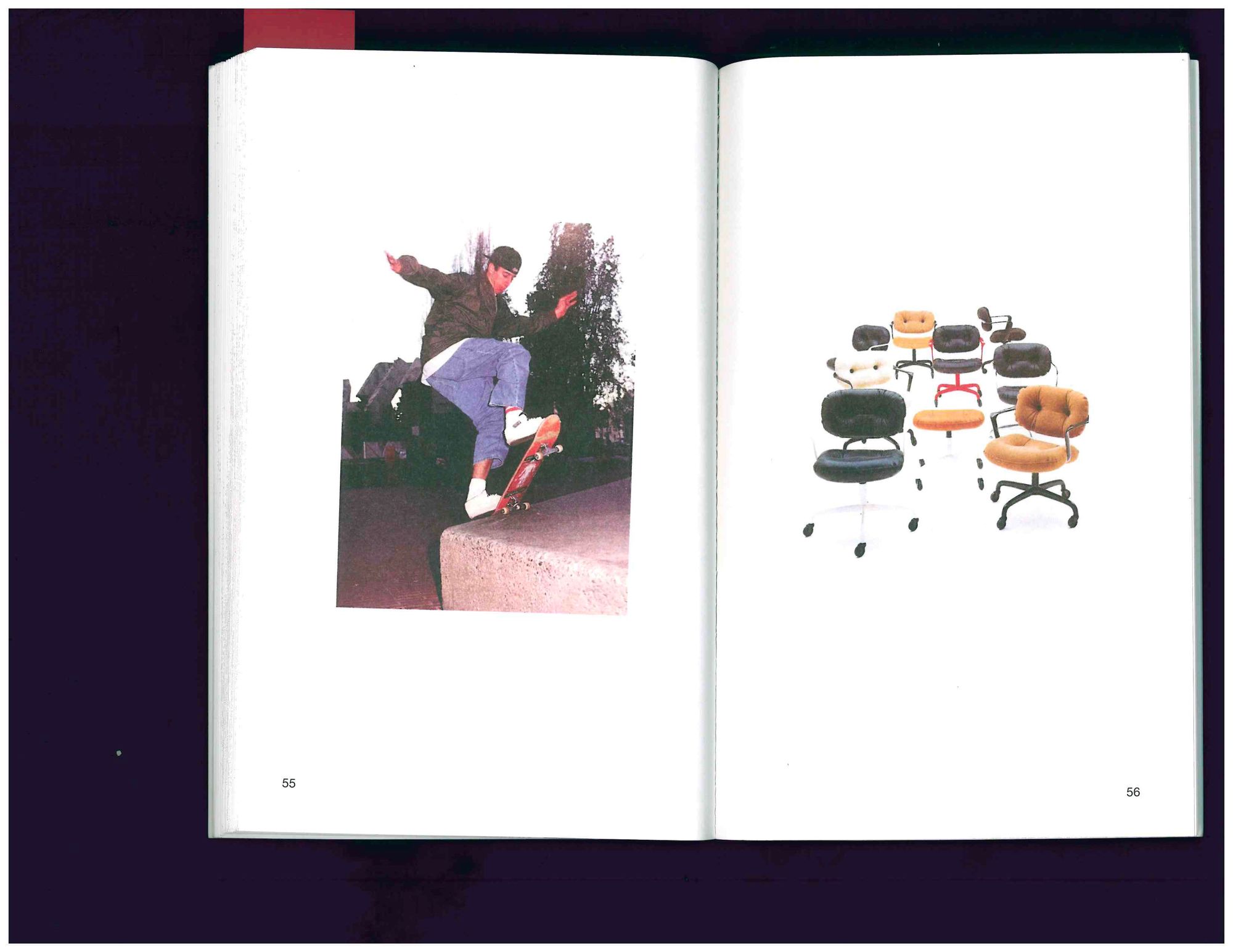

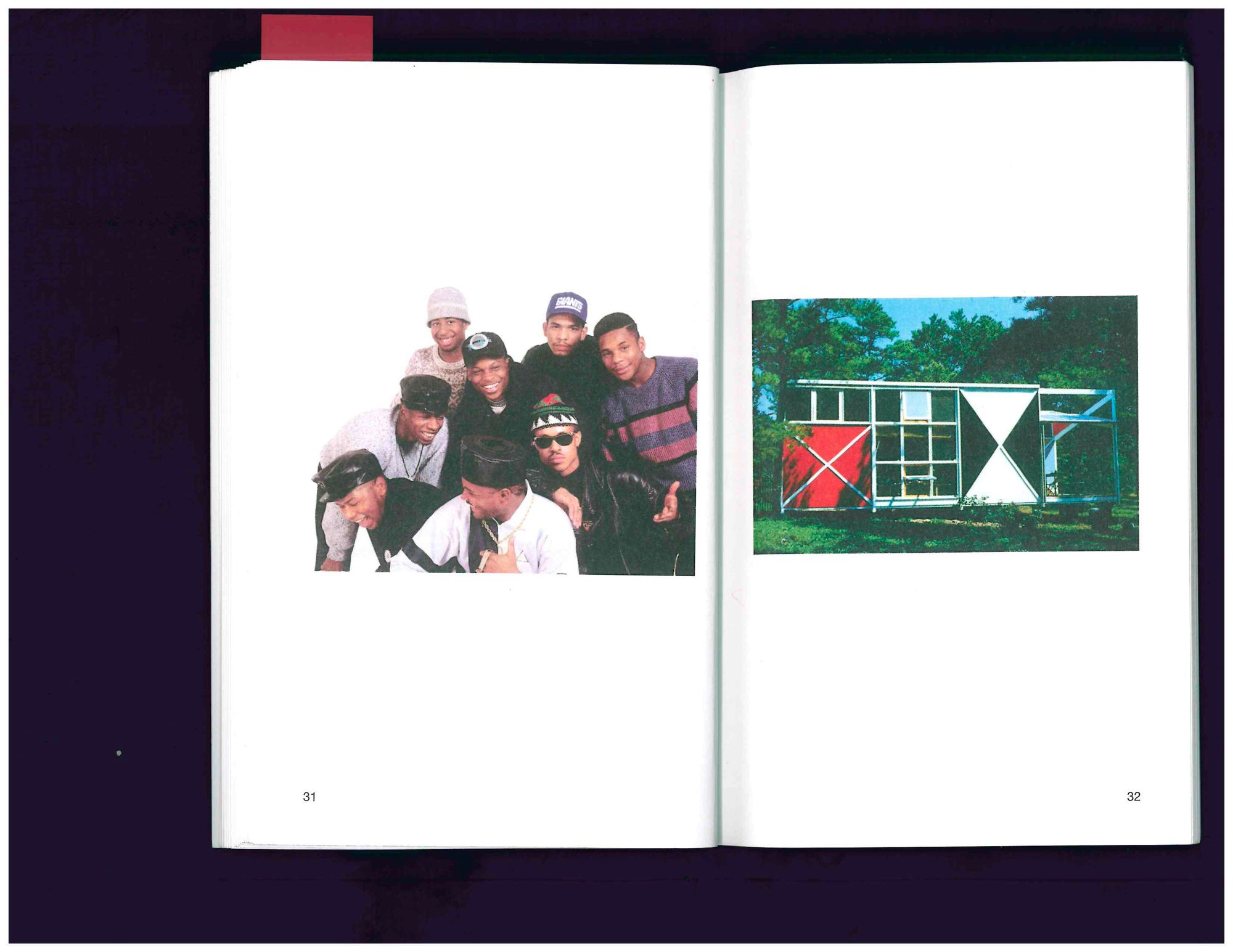

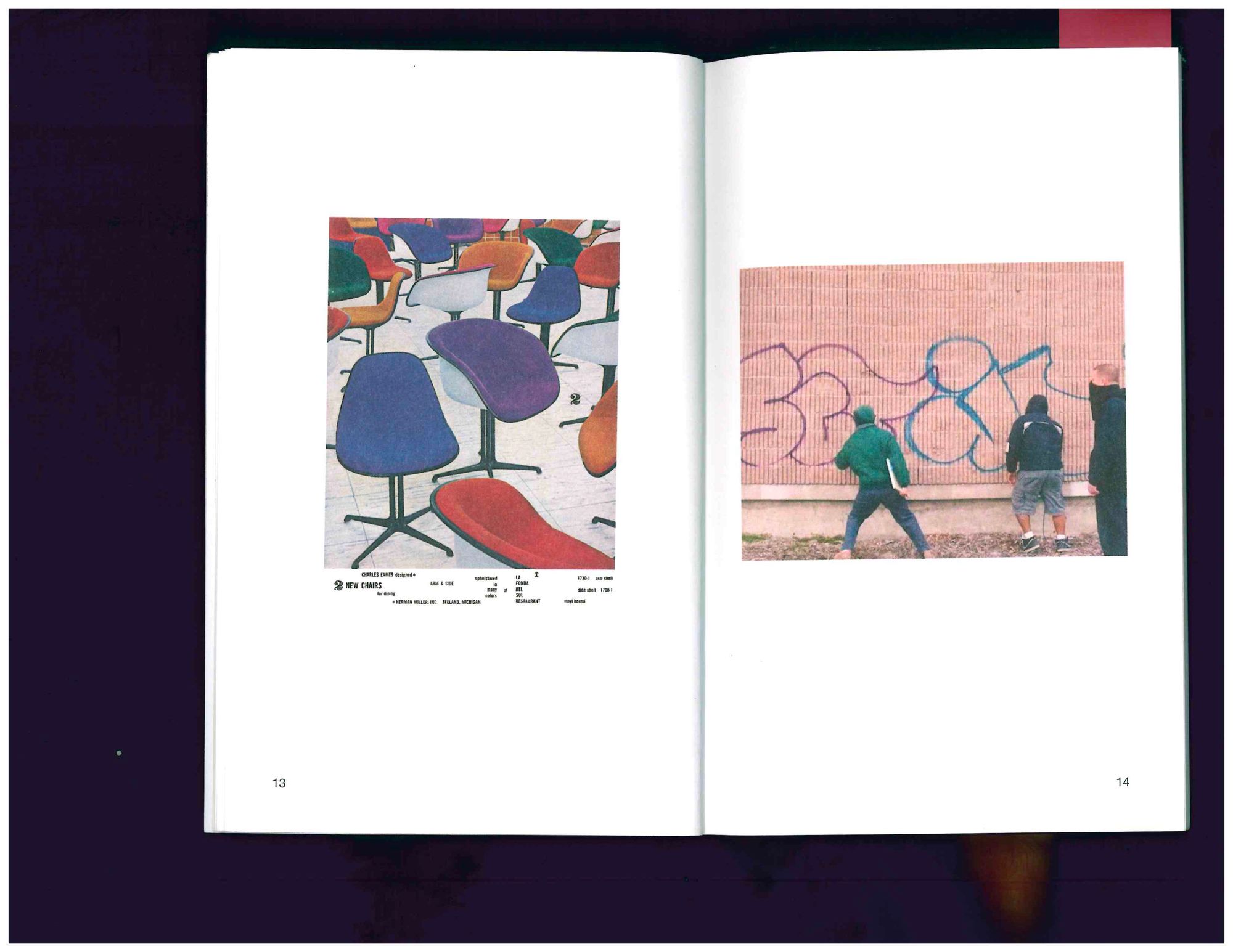

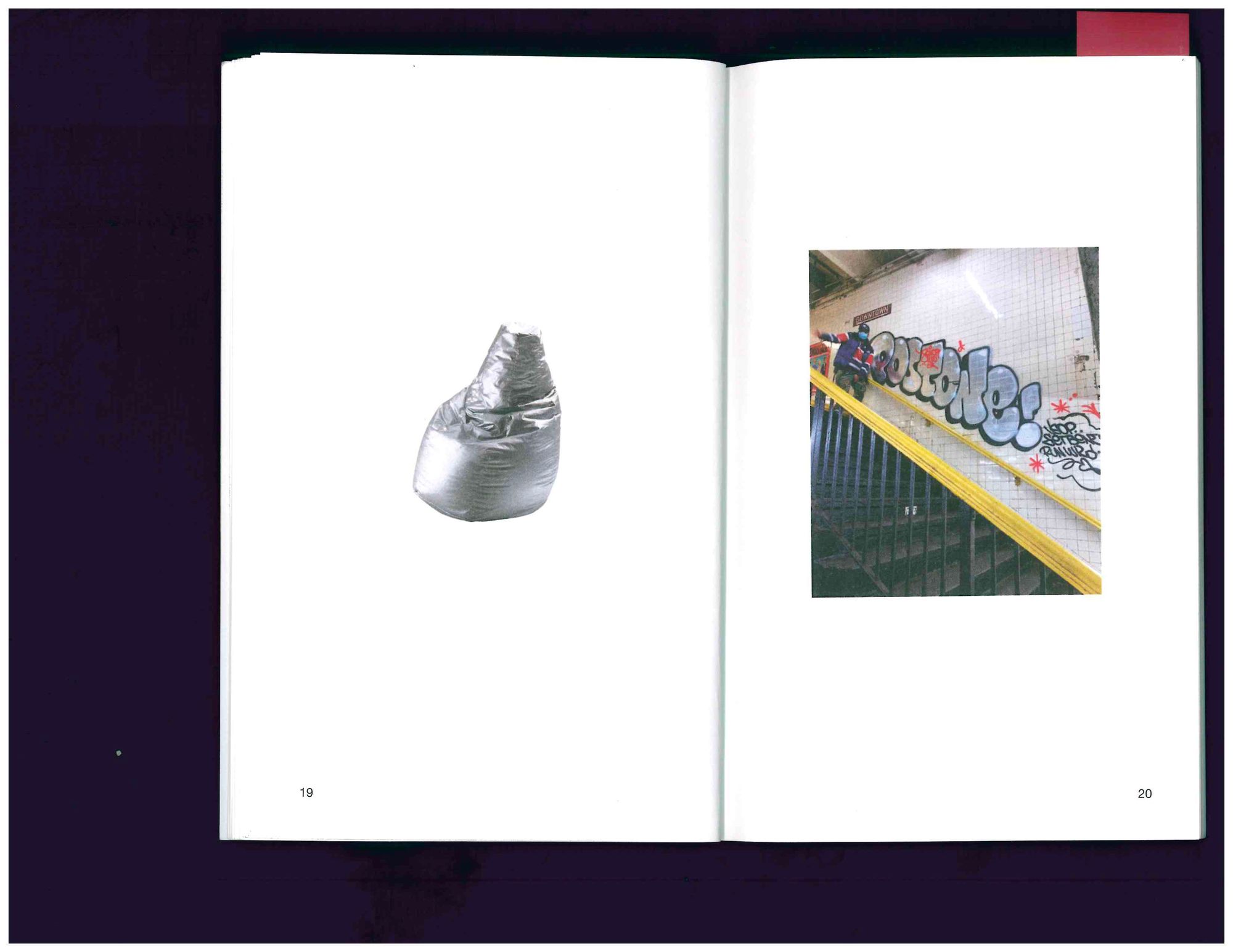

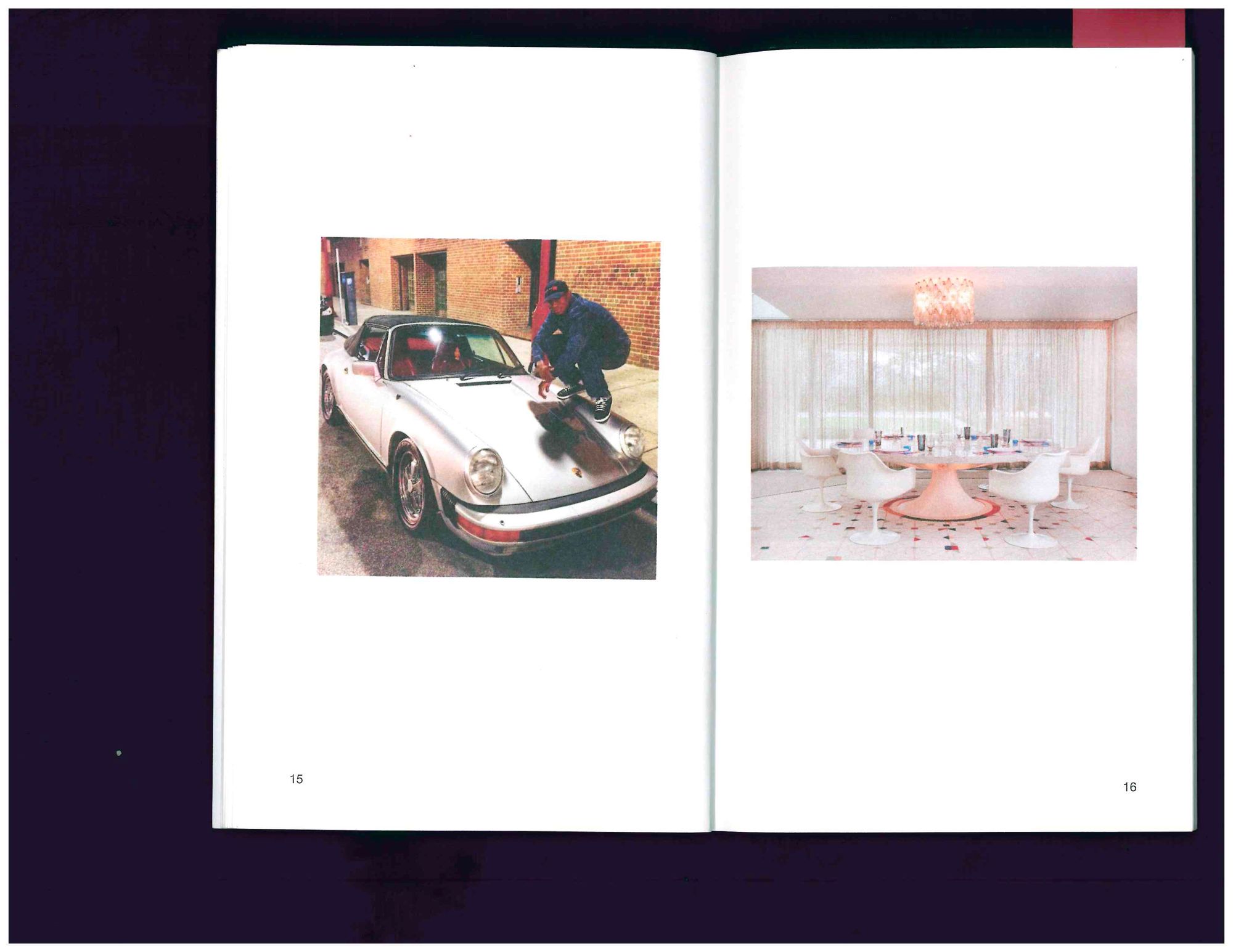

It’s the most powerful for me. The book contains images I’ve been observing for a long time, some as far back as the early 90s. But I began the collection in 2006, the year I founded my office. I created a folder on my desktop called seeing where I dumped anything that spoke to my heart and brought me joy. On rainy days, or if I was getting frustrated about work, I would open it up and look at the images. For a long time it was only design images — I had other folders for graffiti and for skateboarding. At one point I decided my interests had to be whole, that accepting their totality was the only way to be honest with myself, so I dumped all the images into one folder, which made a big mess. To launch my book Selected Works we hosted a dinner in my friend Andrea Lenardin [Madden]’s airplane hangar at Whiteman Airport in Pacoima. She asked me for images to project on the wall, so I gave her the seeing folder, which had never been shown before. Andrea decided to use two projectors to pair images against each other, but the selection was random. That night, watching the slides playing quietly in the background over dinner, it occurred to me that all these images form a consistent visual language — my universe. For the book version of Seeing I decided to make the image pairings more intentional, for example placing [professional skateboarder] Keenan Milton next to Francesca Breuer [daughter of Marcel Breuer]. Milton is shown skating on a Los Angeles schoolyard picnic table in an ad for Chocolate Skateboards — there are thousands of these tables in L.A. schools, with fiberglass tops and sheet-metal bases, and they’ve become iconic in the world of skateboarding. The young Francesca Breuer is also shown in an advertisement, for Knoll, sitting on a Cesca at the Breuers’ home in Connecticut. Both the picnic table and the chair choreograph the bodies and postures of Keenan and Francesca, but there is also innovation at play in each image. Keenan does a switch frontside crooked nose grind across the picnic table, perhaps an NBD trick at the time [NBD is a skateboarding acronym for “never been done”], and it’s debated whether Breuer or Mart Stam designed the first cantilevered chair, also an NBD. Both design and skateboarding have this drive to plant a flag, to do the impossible. Seeing underscores many of the overlaps between these seemingly disparate cultures I grew up in.

The way you describe these scenes is as much about space and context as about individual objects. I’m curious about your work experiences in the early 2000s with Martin Margiela in Paris and Konstantin Grcic in Munich. Margiela is so much about creating a total space, whereas Grcic focuses entirely on the individual object. In your own work, do you have a preference?

There is an Eliel Saarinen quote that shaped my point of view on the relationship between objects and spaces: “Always design a thing by considering it in its next larger context: a chair in a room, a room in a house, a house in an environment, an environment in a city plan.” This is fundamentally different from Ernesto Rogers’s “From the spoon to the city,” which implies you design everything. I personally couldn’t be bothered to think about spoons — anything a body can’t rest on is too small. But in Saarinen’s view, you’re always looking at things in context.

It’s an ecology.

It’s a fabric. Objects have a profound effect on our perception of the spaces around them. Florence Knoll put this well: “Placement and scale of furniture can alter the basic proportions of a space: for example, a small, low-ceilinged conference room will appear higher, and both the furniture and room will seem to be in better proportions if the table height is lowered.” So now we’re getting into, “Adjust the table, you perceive the room differently.” These are excellent rules to play by. What I bring to the game is a set of attitudes — informality and disobedience — and interests — technical rigor and typological invention — that structure the relationship. Another quote I like is from Eames: “Win by playing by the rules.”

Olivares presented Aluminum Bench at Chicago’s Volume Gallery in 2015 amid drawings by Nathan Antolik elaborating on the furnishing’s possible shapes. The bench was created along with architecture fabricator Zahner — atypical for a designer, but quintessentially Olivares in working with specialists outside the furniture field. Photo by Aron Gent.

All three quotes are from prominent midcentury designers. Do you think design thinking is stuck in the mid-20th century?

Industrial design as a discipline connected to the built environment was born in the 20th century. So many important discoveries were made. Once humans discover fire, they’re not going back. You don’t want to ignore discoveries of the past, but at the same time you don’t want to be stuck in the rear-view mirror. Today we practice under very different and dynamic social, cultural, technological, and ecological circumstances that make our work unique to our time. Design is also very much about building on what has been done before, and I live by one of Jim Jarmusch’s five golden rules of cinema: “Nothing is original. Steal from anywhere that resonates with inspiration or fuels your imagination. Devour old films, new films, music, books, paintings, photographs, poems, dreams, random conversations, architecture, bridges, street signs, trees, clouds, bodies of water, light, and shadows. Select only things to steal from that speak directly to your soul. If you do this, your work (and theft) will be authentic. Authenticity is invaluable; originality is non-existent. And don’t bother concealing your thievery — celebrate it if you feel like it. In any case, always remember what Jean-Luc Godard said: ‘It’s not where you take things from — it’s where you take them to.’”

You’re the king of quotes!

I can scrap with quotes.

What do you like about them?

I like language. I look at quotes as building blocks. I remember going to London’s Design Museum in 2003 to see a Peter Saville exhibition and there was another show throughout the common spaces with quotes from designers like [Achille] Castiglioni or [Vico] Magistretti hanging from the ceiling. This was before digital cameras, so I was walking around with my notebook writing down all the quotes, when this older French man came up to me. He was irritated, “Oh, it’s not about that, you shouldn’t take these quotes so seriously.” The experience made me hunker down, like, “Oh yeah dude, actually, it is about these quotes.”

Jonathan Olivares photographed by Caroline Tompkins for PIN–UP 33.

This issue’s theme is “New Americana,” so I have to ask what it means to be an American designer in 2022.

You want the long-winded or the short-winded answer?

Long-winded, of course.

It’s a personal question and a personal answer. I would have to go back to a couple of moments that were formative and pivotal for me. After my junior year, and then again after graduating from Pratt, I worked in Europe. It’s a more balanced lifestyle, honestly, I think people are happier. There aremany more family-owned dynamic design companies as well as institutions and publications that support design than we have in the U.S. Many of those designers and companies see furniture as part of the larger cultural landscape — I’m thinking about Moroso furnishing the Palais de Tokyo in the early aughts, or when Konstantin [Grcic] outfitted the café at the Haus der Kunst in Munich with his designs for Magis, or Jean Nouvel’s furniture for the Fondation Cartier, or the collaboration between the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam with Atelier Van Lieshout. These are just some examples, but they are emblematic of the proximity between culture and furniture in Europe, and highlight the distance between these things in North America, where relatively few comparable examples exist. Living in Europe in the early aughts, it was amazing to work in a design studio that bridged art institutions and furniture manufacturers so fluidly. It would perhaps have been easier to continue practicing in this setting, but after a time I developed my own cultural crisis and realized I didn’t want to live and work there.

Why not?

I wanted to roll up to the skatepark and hear the kids listening to hip-hop. I wanted to walk into Home Depot at 3 am, buy a screwdriver and then eat at a 24-hour diner. These are cultural dimensions and conveniences that didn’t exist in Europe in the same way. Another thing is that my father is from Mexico, so I grew up in a bicultural home, and it took me a long time to identify as American. It wasn’t until this period living in Europe that I realized that being American is a mentality, not about where you or your parents were born or what language you speak. The mentality revolves around ingenuity, convenience, the tension that exists between the extremes of the wealth discrepancy, a certain level of swagger and optimism. Once I began identifying as American, I felt a strong desire to be here, to practice design here, to be part of the fabric of American design. That’s also why I moved to L.A., which is as far as you can get from the European societal model before you hit Asia. I belong in that landscape. That’s where I’m happiest. Moving back to the U.S. in 2006 was a formative moment for me when I realized I could only exist as an American designer. But I lacked the model for what that would even look like. The designers I knew and had visited — Jasper [Morrison], Konstantin, and Ronan and Erwan [Bouroullec] — practiced in that privileged cultural landscape I described earlier, and the opportunities in North America were just very different. With very few exceptions, the designers in the U.S. worked for corporate design consultancies, which didn’t interest me at all. In some ways I felt design had skipped a generation here.

How?

Well, to find independent designers who had worked with American industry in a highly authored way I had to go back to my grandparents’ generation. I met Don Chadwick, Niels Diffrient, and Richard Sapper, who was German but had been the chief design consultant to IBM and had a house in Hollywood. Incidentally, it was my friendship with Don that gave me the idea to move to L.A., and visiting Richard in Beachwood Canyon that inspired me to choose Hollywood. Richard’s work for Knoll and IBM was outstanding — we did a 50-hour interview about it that was published as a book. I then edited a book of Don’s photography of Los Angeles. It shows you that he approaches design with cultural ideas — he’s not just an industry pawn but someone who reshaped the industry with artistic intention. This generation helped me see how design could be done in America, what practicing design within the structures that are in place here looks like. Again, it doesn’t matter where you’re from — I’m a Mexican from Boston who discovered design in Europe — there are structures in the U.S. that dictate how design manifests here, and if you work within those structures you are practicing American design.

For his 2019 design for Spanish footwear brand Camper’s midtown flagship, Olivares designed long displays made of Indiana limestone — the material used on the building’s 1930s façade. The large neon logo flows with the shop’s clear view of Radio City Music Hall to read “Camper Radio City.” Photo by Daniele Ansidei.

Why did you your dad come to the U.S.?

My parents met and married in Tapachula, Chiapas, Mexico in the 70s. Their idea was to move to Boston for a year so my dad could learn English. He liked it, so they stayed. I was born and raised in Boston but spent every holiday and many summers in Mexico City where my father’s family is from. Growing up in a bicultural household, I never felt fully American. Another formative moment in realizing how American I am was at an Eero Saarinen exhibit at Cranbrook around 2008. I had always assumed Eero was more Finnish than American, but in a video of him speaking, his accent and mentality were so American — thinking big, ingenious, swaggering, elegant. He spoke with the same accent as my maternal grandfather, Bob, who was one of my biggest role models growing up. Grampa was cool and calm, he was a mechanic who had taught at a technical high school and been a marine in World War II in the Pacific. I never saw him break a sweat.

In terms of designer legacy, is it better to have made a good chair or produced good books?

For me, the books help build my point of view. I learn a lot from making books and I’m happy that each one shares those learnings withother people. But they could all disappear tomorrow and it would be fine. Ultimately, the legacy comes from the three-dimensional output of things that people can interact with, sit on, live with. How many people do you touch with that? It’s why I love things people rest on because you’re physically hosting a body. A chair especially. It’s such a special scale.

What is it about a chair specifically?

A chair hosts and choreographs a single body, carries an attitude and an outlook on how we live, and speaks about the processes that made it. At its best a chair can make us want to live — to eat, draw, read, pass the time with friends, or sit alone watching the light change in our home throughout a day. A chair carries all these things.

It’s interesting, because a chair is not essential. A bed is.

A bed is far more essential than a chair. But that’s exactly why the chair is so special, because it elevates. If you look at Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the chair is much higher up on the pyramid than the bed. The bed exists on the bottom tier alongside food, water, sleep, sex, clothing, and shelter. On the next tier we have protection, law, employment, property. Then comes family, friendship, and intimacy. The chair may start here, bringing family and friends together. The chair is already three ranks higher than the bed, but it goes further. Esteem, confidence, respect — the chair exists at that level. And it can exist at the top too, where self-actualization, creativity, personal growth, morality, and spontaneity are found. Family, friendship, confidence, respect, creativity, and spontaneity — all of that can happen while you’re sitting on a chair.

Jonathan Olivares Aluminum Chair with Knoll