Wallmakers, 3-Minute Corridor, 2023. Photo by Danko Stjepanovic. Courtesy of Sharjah Architecture Triennial.

DAAR - Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti, Concrete Tent, 2023. Photo by Danko Stjepanovic. Courtesy of Sharjah Architecture Triennial.

About an hour into the Emirati desert, past super-sized malls, mosques, and uninterrupted expanses of sand, is Al Madam, a ghost village that encapsulates with uncanny poetry the critical reflexes of the second edition of the Sharjah Architecture Triennial. The settlement’s linear plan and squat concrete buildings are the bones of a failed attempt to house a local Bedouin tribe in the wake of the UAE’s independence. Hindsight is golden: the locals were nomadic in part because shifting dunes made sedentary life both undesirable and untenable. A decade after construction, the dwellings were awash in sand and abandoned.

In this stunning place, haunted by top-down architectural hubris and modernist state-building, triennial curator Tosin Oshinowo’s titular theme The Beauty of Impermanence: An Architecture of Adaptability finds metaphoric manifestation. At the center of the sand-submerged village, the winners of last year’s Golden Lion, DAAR — Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti — constructed a new iteration of their Concrete Tent. The installation solidifies a mobile tent into a concrete house to represent the permanent impermanence of Palestinian life at the Dheisheh Refugee Camp near Bethlehem. After the Triennial, the tent will be washed over by the desert sands, too. Yet, in a tragic embodiment of the second theme in Oshinowo’s title, adaptability, Hilal and Petti transformed their Concrete Tent into an ad hoc space of mourning for the ongoing slaughter in Gaza. During the opening weekend, a chilling audio recording recited the ceaselessly expanding list of Palestinian children killed since the start of the current Israeli invasion. Shoes off, sitting on cushions and carpets, people wept.

Yussef Agbo-Ola, JABALA: 9 ASH CLEANSING TEMPLE, 2023. Photo by Danko Stjepanovic. Courtesy of Sharjah Architecture Triennial.

To a certain degree a spiritual offspring of Lesley Lokko’s Africa-centric 2023 Venice Biennale (Lokko, in attendance, led a Keynote chat), the current Sharjah Triennial calls for “new model of thinking…born out of scarcity rather than abundance,” according to Oshinowo’s curatorial statement. Her selection of twenty-nine exhibitors spotlights small practices from the Global South and its diasporas, prioritizing contextual solutions over technical innovation, all with a strong ecological bent.

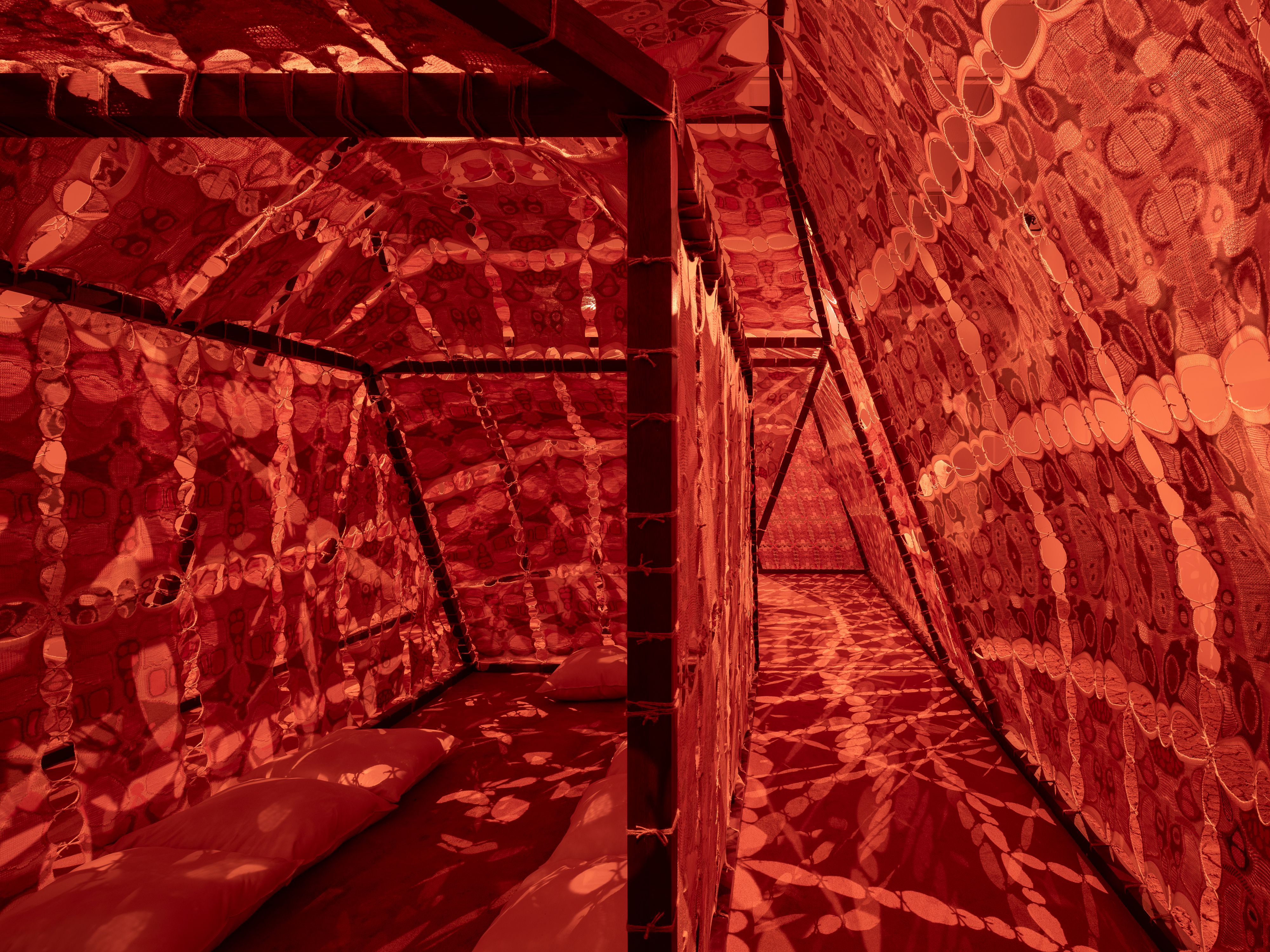

Continuing the trend of architecture exhibitions straying further from academic practice and closer to art practice — fewer models, more vibey installations — the main Triennial venue, the Al-Qasimiyah School, hosted a number of sensory, materially-experimental entries, such as 1:1-scale mud-caked tire structures by Kochi’s Wallmakers or Yussef Agbo-Ola’s JABALA: 9 ASH CLEANSING TEMPLE. Described as a “living architectural entity for homing non-human life and endangered species in the womb of a sacred mountain”, the jute and hemp temple-room is mesmeric but also confusing — where and what exactly are we talking about? In contrast, the installations with the most teeth were those situated in urban reality, such as Sandra Poulson’s exploration of dust as a marker of spatial and class divisions in Luanda, Angola, from colonial times until now. Coating the floor and papier-mâchéd ephemera like clothing, cookware and fruit with thick layers of odorous brown dust, Poulson stages an arresting scene that evokes the sensory experience of a Luandan street market.

Wallmakers, 3-Minute Corridor, 2023. Photo by Danko Stjepanovic. Courtesy of Sharjah Architecture Triennial.

Adrian Pepe, Utility of Being: A Paradox of Proximity, 2023. Photo by Danko Stjepanovic. Courtesy of Sharjah Architecture Triennial.

Like Al Madam, the Al-Qasimiyah School is a relic of Sharjah’s post-independence modernist push — albeit a more successful one. Newly renovated for the Triennial, its breezy halls and shaded courtyards demonstrate the effectiveness and attractiveness of passive vernacular design in an extreme-heat environment. Standout exhibition design and communal seating arrangements by Space Caviar add an industrial-chic flair to the 70s-era concrete structure.

The shadow of politics, or their uncanny absence in the Gulf, seemed to hang over the inaugural weekend in Sharjah back in November. Donning a keffiyeh and pointed words about Gaza, Hoor Al Qasimi, President and Director of Sharjah Art Foundation (and daughter of the Emirate’s leader) underscored the importance of critical platforms like the Triennial in a region usually bereft of them. Yet if Lokko’s 2023 Venice Biennale felt vaguely utopian in the face of the challenges facing the Global South, Oshinowo’s “scarcity” framing and the geopolitical environment in the Middle East lend a heavy realism to the exhibition in Sharjah. “The cornucopian model is unsustainable,” Oshinowo proclaimed at the opening ceremony. The resource-ravenous model of industrial and urban expansion inherited from the West is destroying our planet. While her commitment to this perspective is sincere, the irony of uttering it within a developmentalist petrostate went unacknowledged.

Limbo Accra, SUPER LIMBO, 2023. Photo by Danko Stjepanovic. Courtesy of Sharjah Architecture Triennial.

Cave_bureau, Anthropocene Museum 9.0, 2023. Photo by Danko Stjepanovic. Courtesy of Sharjah Architecture Triennial.

One distinction of surprising relevance to the Triennial’s positioning is the identity of its sponsoring Emirate, Sharjah. If Dubai is an international hub known for glitz-and-glam, Sharjah is its low-key, religious neighbor housing many of the migrant laborers toiling on Dubai’s towers. In line with this dichotomy, Sharjah is starting to embrace its heritage rather than razing it, with the Triennial as a major catalyst. Beyond Al Madam and the Al-Qasimiyah school, this year’s Triennial spreads across other disused urban sites to great success, both conceptually and artistically. In the void of a half-built shopping mall, Limbo Accra drapes cascading arches of white fabric to draw attention to buildings across the Global South left incomplete due to speculation, mismanagement, or economic malaise. In Sharjah’s delightfully named sub-zone “Industrial Area 5”, Papa Omotayo and Eve Nnaji of MOE+AA/ADD_apt build a whimsical tower of stacked birds’ nests and plant material that literally brings life to the otherwise lifeless district. The most intriguing urban off-site is the city’s old slaughterhouse, occupied by the newest edition of Cave_bureau’s Anthropocene Museum project and an unforgettable series of blow-up Awassi sheep pelts by Adrian Pepe. Visitors follow the route of a sheep deeper into the public slaughterhouse, designed with halal-architectural precision. In moments like these, when visitors engage with the Emirate’s built context and cultural history, the Triennial finds its finest curatorial expression — embracing what is locally known rather than dictated from afar.

Sharjah Architecture Triennial 2023 Opening, Al Qasimiyah School, Sharjah, UAE. Exhibition Design by Space Caviar. Image by Edmund Sumner. Courtesy of Sharjah Architecture Triennial.

Arquitectos, Play You Are in Sharjah, 2023. Photo by Danko Stjepanovic. Courtesy of Sharjah Architecture Triennial.

By asserting itself as a platform for architecture in the Global South, the Sharjah Triennial naturally opens itself up for conversations about what “decolonial” really means. This year, brise-soleil became an unlikely motif capturing the debate. In one instance, Thao Nguyen Phan’s video work, First Rain, Brise Soleil, follows a fictional Vietnamese construction worker who specializes in the concrete latticework gracing buildings in hot climates around the globe. The form popped up again in Sharjah Art Foundation’s open-air theater, where a screening of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s excellent film, Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Power in West Africa, pointed to the “imperial history” of the Architectural Association’s (AA) influential Department of Tropical Architecture during the last breaths of British colonialism. While post-independence leaders also championed tropical-modernist forms, the film directors — in attendance — painted a complicated portrait of this exchange. Should elements like brise-soleil be interpreted as a vernacular mode or a symbol of colonial experimentation? A Cuban architect in the audience objected: had the research team considered Latin American countries, already independent for two centuries? In the Americas, modernist towers adorned with brise-soleil often read like state-building marks of anti-imperialism and socialism. Discursive moments like these demonstrate both the challenge of gargantuan concepts like the “Global South” and how Sharjah, a money-loaded melting pot of people and power, has become an exciting architectural forum for it.

RUÍNA Architecture, Time Transitions, 2023. Photo by Danko Stjepanovic. Courtesy of Sharjah Architecture Triennial.