FREDDY MAMANI’S CHOLET CULTURE

by Thom Bettridge, Jonathan Castro

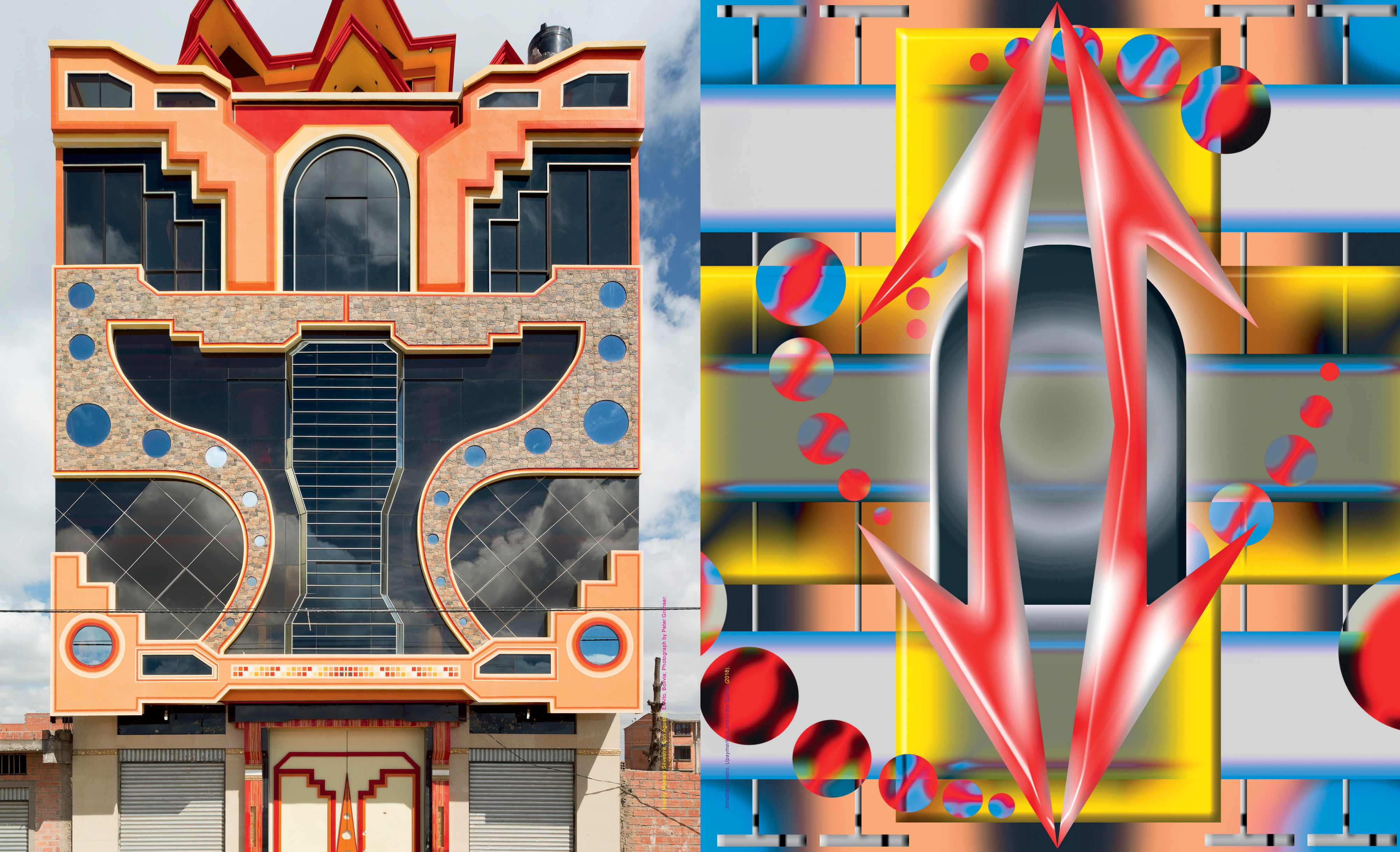

Left: Freddy Mamani Silvestre, Crucero del Sur, El Alto, Bolivia; Photography by Peter Granser. Right: Jonathan Castro, Ajayu (Main Soul) (2018).

Seeing the work of the Bolivian architect Freddy Mamani Silvestre for the first time is like being radicalized by a mirage. The photographs that have been circulating of his cholets — a remix of the words “chalet” and “cholo” (the latter an often-pejorative term meaning “mixed-race”) — are intensely maximal to the point of seeming unreal. The alien-ness of Mamani’s buildings isn’t only a product of their color or patterning, but also stems from the notion that something so radically outside the palette of the global standard of taste could be built on such a massive scale. By an effect of contrast, his cholets reveal the typical design language of late capitalism to be a desert of the imagination, populated by warmed-over interpretations of sleep-walking Modernism buttressed by athleisurely notions of the good life.

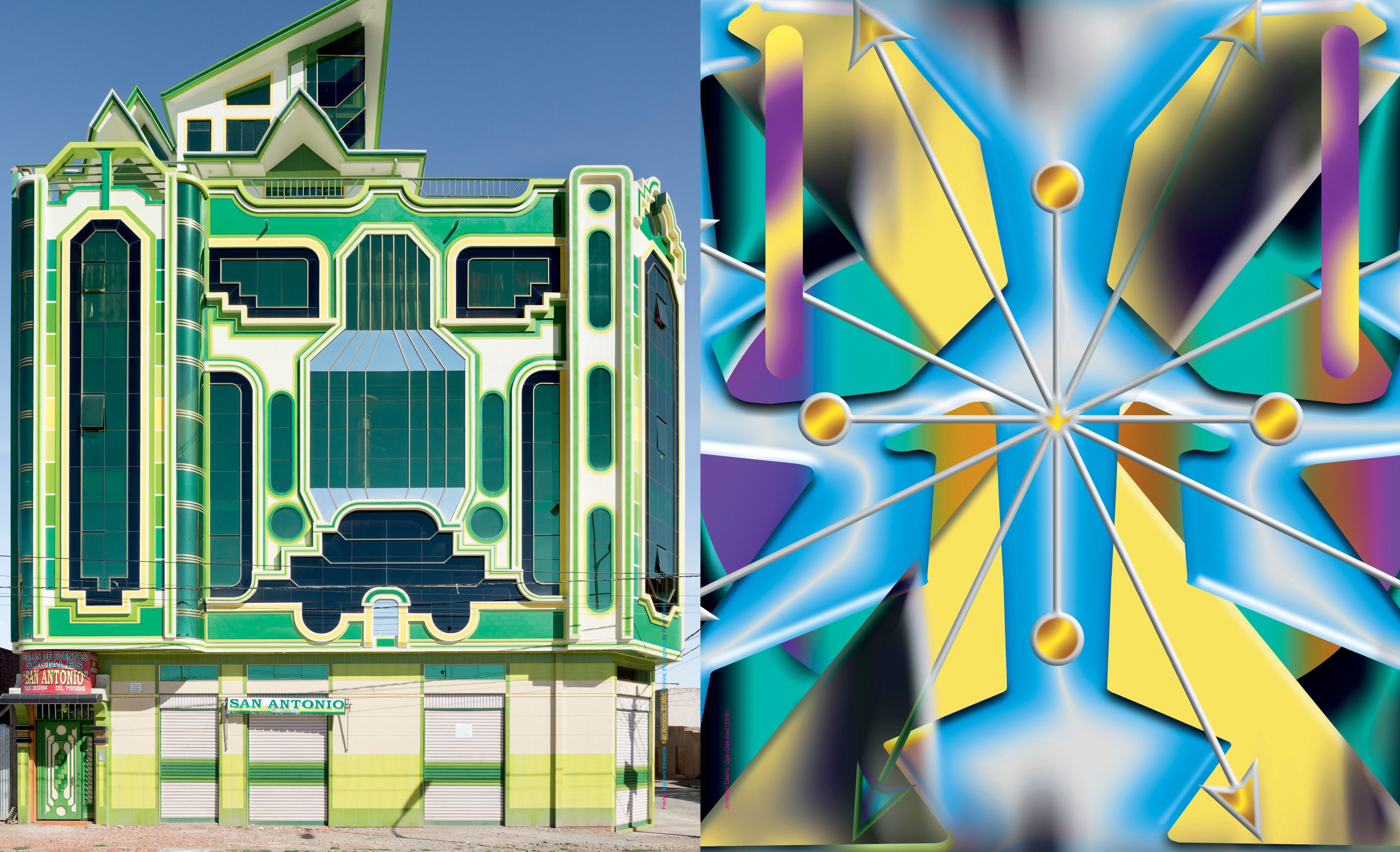

Left: Freddy Mamani Silvestre, Don Agustín, El Alto, Bolivia; Photography by Peter Granser. Right: Jonathan Castro, Upaymarka (Lad of the Spirits) (2018).

Since 2005, the self-taught, 46-year-old architect and former bricklayer has been erecting cholets by the dozen, with over 60 of them now dotting the skyline of El Alto, a swelling Andean metropolis located 13,000 feet above sea level immediately adjacent to Bolivia’s capital, La Paz. The majority of Mamani’s cholets function like self-contained chimneys for capital, built in the service of El Alto’s newly emerging Aymara bourgeoisie. Typically they comprise commercial space on the ground floor, lavish ballrooms on the second floor, and apartments above, a combination intended to ensure their financial sustainability. But it’s not the all-in-oneness of the cholet that makes it so unusual, rather Mamani’s employment of symbolism and color instead abstraction as his primary architectural language — a code that derives from a convergence of the indigenous iconography of the Aymara people and the fantastical lexicon of science fiction.

Left: Freddy Mamani Silvestre, San Antonio, El Alto, Bolivia; Photography by Peter Granser. Right: Jonathan Castro, Ojje (Oqe Boy) (2018).

On reaching out for comment to Mamani, I received only the following WhatsApp reply: “Hola Thom, estoy muy alejado de la ciudad y no tengo una buena línea” (“Hi Thom, I’m very far from the city and don’t have good service”). So in lieu of an oral account, the following portfolio, exclusive to PIN–UP, is a visual exploration of the symbolic language of Freddy Mamani dissected through the graphic designs of Peruvian-born Jonathan Castro, a cholo celebration of mixing and diversity by two Andean maximalists who are pushing forward into new aesthetic terrains.

Left: Freddy Mamani Silvestre, "La Vicuñita", El Alto, Bolivia; Photography by Peter Granser. Right: Jonathan Castro, Willka Uta (House of the Rising Sun) (2018).

“The thing you have to understand about a symbol is that it has a soul behind it,” says Jonathan Castro, a Peruvian artist and graphic designer living in Rotterdam. Castro’s work, like Mamani’s, melds the indigenous iconography of the Andes with futuristic textures. “In a world that is a complicated as ours, something that is as minimal as an Apple Store looks like marketing and feels like a lie,” Castro continues.