HEAT.SEAT, thermo-sensitive furniture by J.MAYER.H. In the permanent collection of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Photo: J.MAYER.H courtesy Galerie Magnus Müller, Berlin.

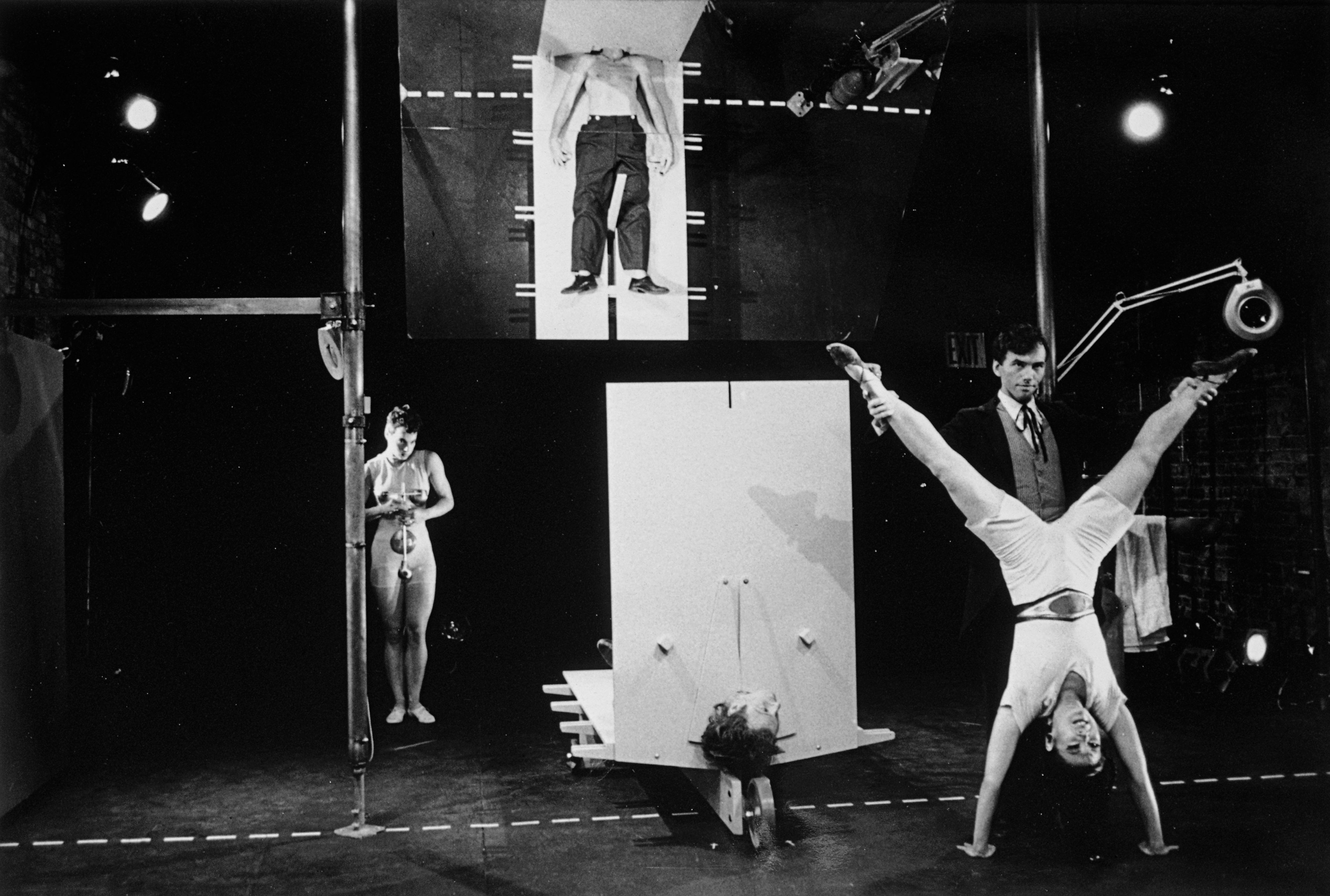

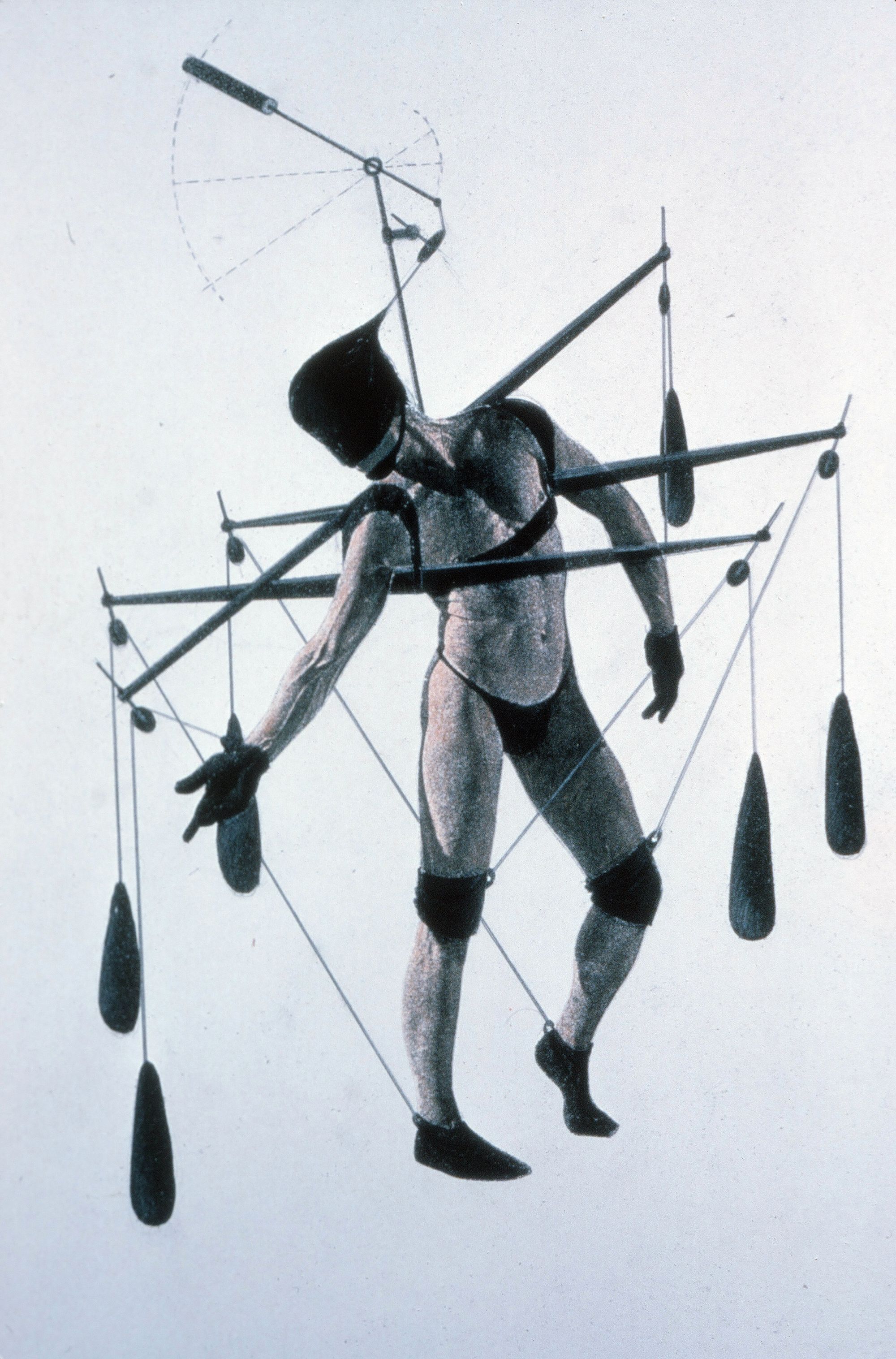

The Rotary Notary and His Hot Plate by Susan Mosakowski, set design by Diller + Scofidio, 1987. Performance view, La Mama E.T.C., New York, June 3, 1987. Produced by Creation Production Company. Photo by J. Vezuzzo.

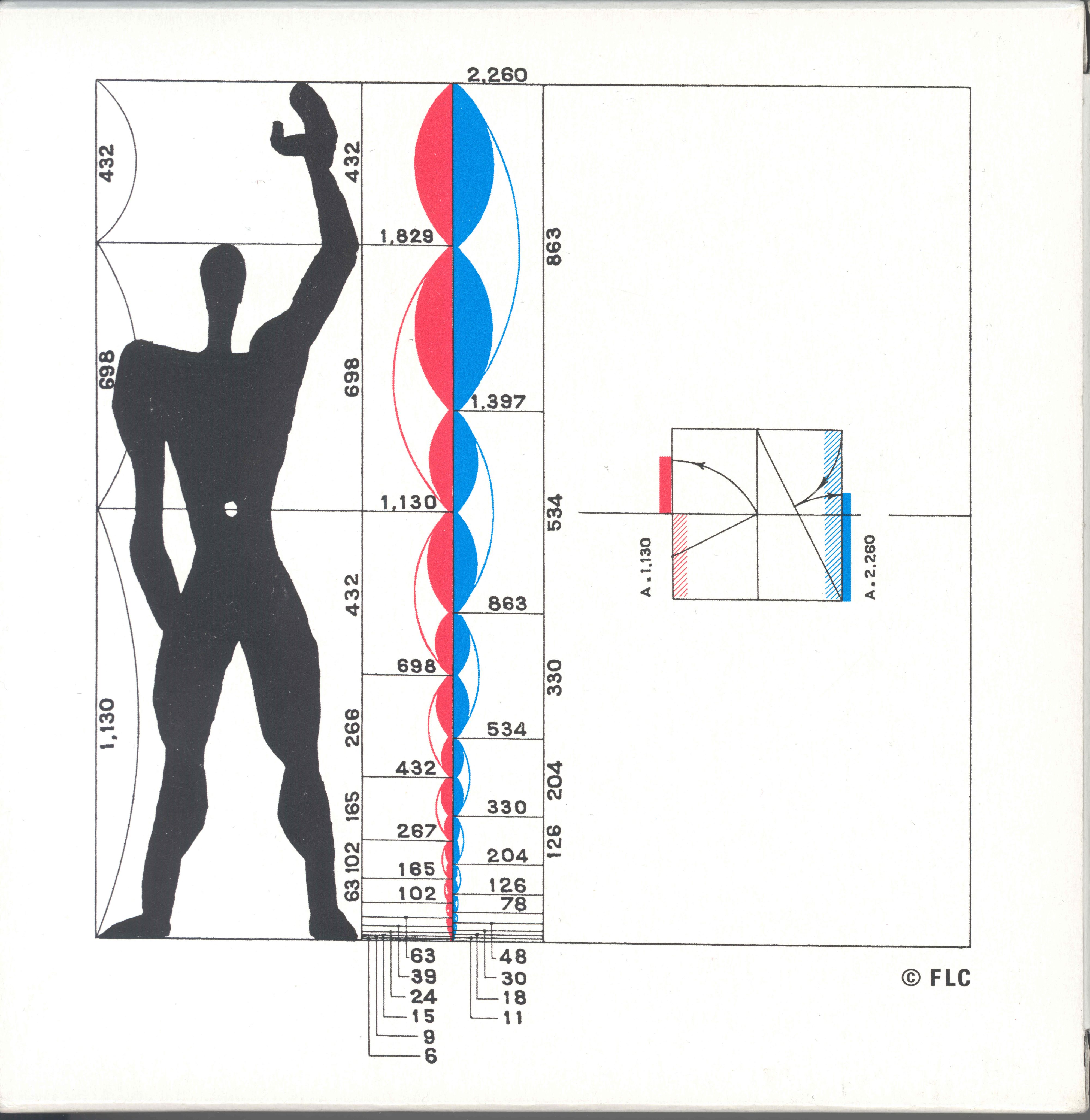

The body has long played a central role in architectural thought systems: as the thing sheltered, and the thing disciplined; in the diagrams of da Vinci by way of Vitruvius; and likewise in Le Corbusier’s man-sized Modulor. But, at the end of the 20th century, a new kind of architectural discourse emerged, at times using “the body” as a fixed phrase, spawning all manner of contemporary and retrospective exhibitions and texts. From the vantage point of the 21st century, many have attributed the discursive shift of the 1990s to the opportunities and anxieties engendered by emerging technologies, among them the Internet, cosmetic surgery, parametric design tools, digital photo manipulation, genome mapping, new pharmaceuticals, and virtual reality. In today’s era of VR headsets and metaverse real-estate sales, of deepfakes and large-language models, of drone surveillance and at-home genetics tests — not to mention the coronavirus pandemic — last century’s body talk is worth revisiting.

As early as 1977, marketing copy for Kent Bloomer and Charles Moore’s book Body, Memory, and Architecture (Yale University Press) argued that, despite its place as “the divine organizing principle in the earliest built forms,” the body had faced a “near elimination from architectural thought in this century.” Though the authors clearly had a short memory, since Modernism’s love affair with hygiene is well attested (as Le Corbusier declared: “BIOLOGY! The great new word in architecture and planning!”), postwar pharmacology had indeed relegated the body to a more minor place in architectural discourse by the third quarter of the second millennium.

Le Corbusier's 1945 diagram the Modular divides the height of the average man into golden ratio proportions to produce a scale of measurements for his architecture.

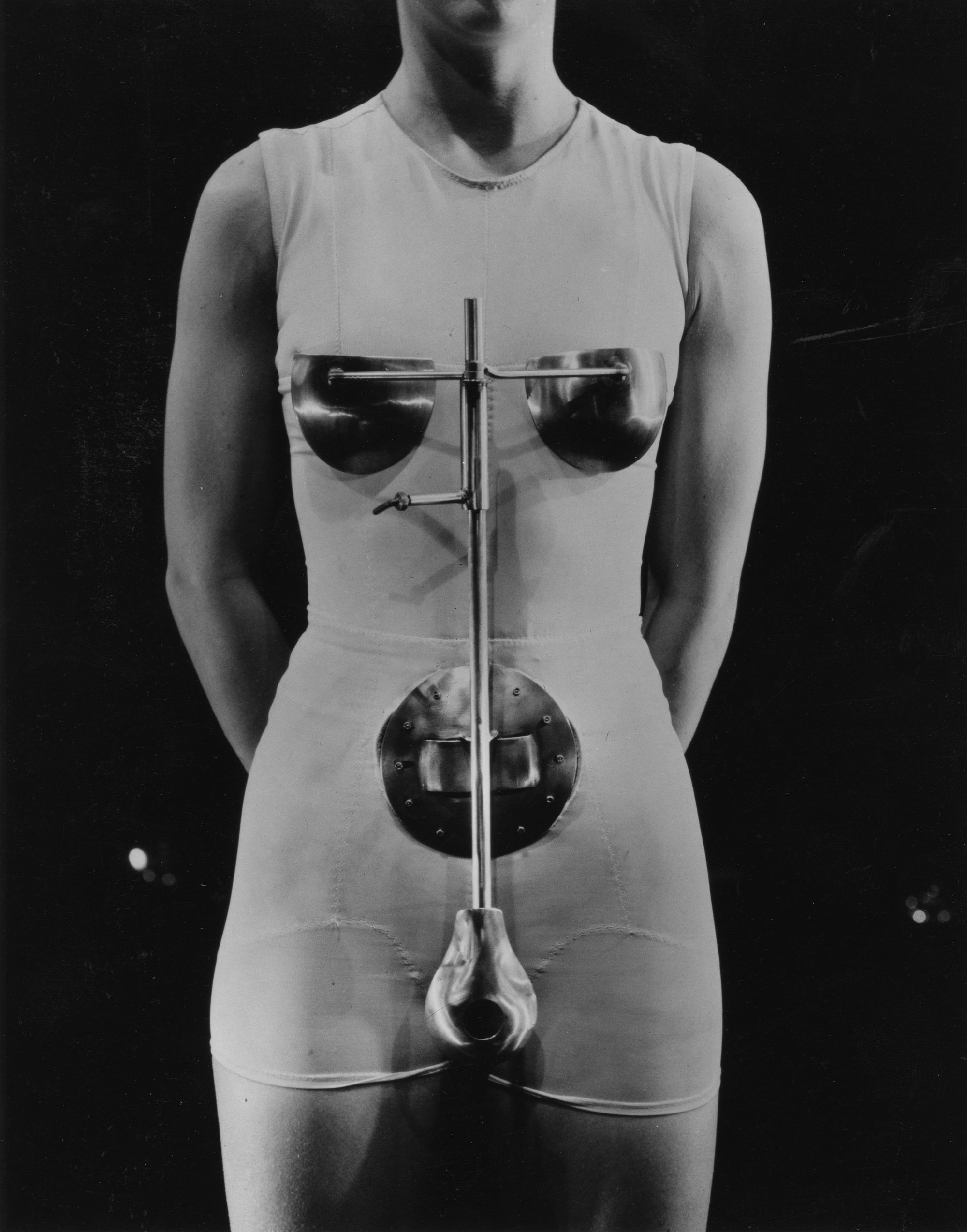

Among the vanguard of its comeback were Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio, whose work has included “automarionettes” and armor (for The Rotary Notary and His Hot Plate, 1987), flesh-embossing seats (Para-Site, MoMA, 1989), and sensory reorganization (Blur Building, 2002). Storefront for Art and Architecture displayed their multimedia work as the solo show Bodybuildings in 1987, but Diller says that any critique of the field and its purported body ignorance was at most implicit. “I took a position someplace between art and architecture,” she recalls. Inspired by performance artists like Chris Burden and Vito Acconci, she and Scofidio were also reacting against the “puritanical” norms of their education. As a student, she “started to think about where the body was performing in space, and I was starting to close the gaps a bit. The irreducible unit of space is between a body and a mirror or a painting or a wall or another human, so the body is an irreducible constant from which there is a set of relations.” Those relations include measures and movements within “everyday operational space” but also the “everyday conventions” that bodies must navigate or are subjected to.

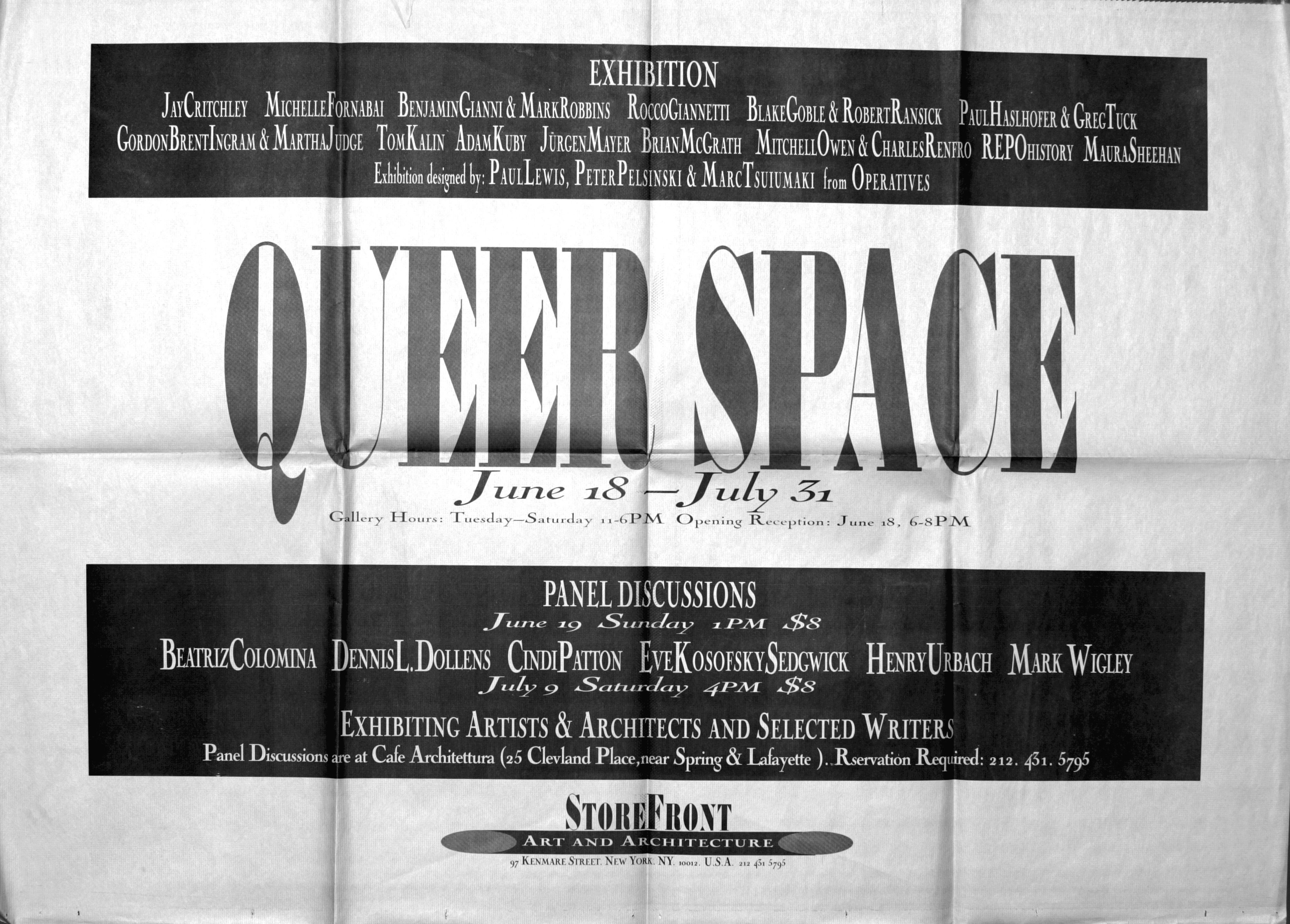

Questioning dominant norms yet further, Storefront staged the 1994 exhibition Queer Space — whose participants included Charles Renfro (of what is now Diller Scofidio + Renfro) — which sought “to rethink the politics of space” and ask if it was “even physical space that is in question, or is it the space of discursive practices, texts, codes of behavior, and the regulatory norms that organize social life?” Indeed, a large segment of 90s body talk focused on identity, especially gender and sexuality: after 1995’s Building Sex: Men, Women, Architecture and the Construction of Sexuality, for example, Aaron Betsky published a 1997 follow-up titled Queer Space: Architecture and Same-Sex Desire.

Jürgen Mayer H., whose HOUSEWARMING temperature-sensitive wall panels and other features reconfigured Storefront for Queer Space, recalls that the body discourse was absent from the academic landscape of his native Germany. It was only during his time at Cooper Union and Princeton in the early to mid 90s, that “it was all about the body and gender issues and critical thinking around them … Part of it was representation of gender in spaces, a lot was also about the performative aspects of space in the programming of it.” Diller also recalls that, when she came to Princeton, “We were thinking about domesticity, about vision and visuality in general,” adding that the male gaze was a major topic in critical theory at the time. Princeton architectural historian Beatriz Colomina was likewise researching gender and architecture: after editing Sexuality and Space in 1992, she brought out her own extended reading of Loos and Le Corbusier, Privacy and Publicity, two years later.

Newsprint poster for the 1994 Queer Space exhibition organized by Beatriz Colomina, Dennis Dollens, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Cindi Patton, Henry Urbach, and Mark Wigley for Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York City. Courtesy Storefront for Art and Architecture.

“I do understand and remember [the body] to have been something that pervaded the humanities and social sciences in the 1980s and 90s,” says John Paul Ricco, a professor of art history and visual culture at the University of Toronto. “In fact, it seemed that there was a decisive turn from language to corporeality.” André Lepecki, chair of NYU’s Department of Performance Studies, likewise notes a marked “prevalence of ‘the body’ in the 1980s and early 1990s in critical theory and art criticism.”

Though Antonin Artaud’s idea of a body without organs had been around since the 1940s, and Gilles Deleuze had discussed it as early as 1969, its big entrée into the anglosphere likely followed the translation of Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s 1980 A Thousand Plateaus. Erstwhile semioticians in art history were pivoting to phenomenology (as October co-founder Rosalind Krauss did with her 1986 work on Richard Serra), while fads in the commercial art world moved from formalist and conceptualist post-studio art to expressionist, figurative painting. English translations of Michel Foucault’s work became fashionable, and by the 90s relational aesthetics was the name of the game. Meanwhile, on the ground, the (art)world was reeling from the AIDS pandemic and architects’ regulations changed with the 1990 Americans with Disability Act.

This architecture-body discourse rose at the tail end of PoMo and high-tech architecture, whose respective imagistic historicism and exposed industrialism would give way to the smooth surfaces and curvaceous, biophilic blobitecture made possible by new computer and manufacturing technologies. Projects came with anatomical names, such as the Copenhagen Hippocampus (Morphosis, 1996) or the Embryological House (Greg Lynn, 1997–2001). In an essay for Skin: Surface, Substance, and Design (2007, Princeton Architectural Press), Ellen Lupton’s retrospective survey of the body in 90s and Y2K design, architect and theorist Alicia Imperiale compares algorithmic 3D software of the time to genetic mutation. “Forms,” she writes, “designed in the space of the computer are analogous to bodies moving in time.”

In 2017, Betsky revisited Queer Space with architect Jaffer Kolb in an interview published in Log. Betsky notes that, despite anticipation of a gender equalization in the 90s, “There’s been an incredible drop-off in gender equality, from first-year architecture students to the profession. Any form of equalization we have seen has also made little difference in the rehabilitation of the interior, in distinctions between inside and outside, and in top-down planning.” And, given “queer” assimilation (primarily white, bourgeois LGBs), “It might be the case now that queerness and architecture don’t intersect anymore, and that’s okay.” As Betsky’s retrospective comments point out, “the body” is always a question of “whose body/ies.” In his 2016 essay (Black) Sexuality and Space: The Body and the Gaze, Mario Gooden, principal of Huff + Gooden, who parallels his performance practice in his architecture, points out that in a field where “black subjectivity is virtually non-existent … Black bodies systematically fall beyond the frame of reference for spatial inclusion.” Rather than (body) discourse expanding the consideration of varied bodies and peoples, “architectural theory represents a space of exclusion of black subjectivity.” Exclusion has been central to architectural practice as it unintentionally or intentionally defines lines of access and quality of life along race, gender, ability, and class. Design affects all bodies, whether one makes it “about” them or not.

HEAT.SEAT, thermo-sensitive furniture by J.MAYER.H. In the permanent collection of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Photo: J.MAYER.H courtesy Galerie Magnus Müller, Berlin.

J. Mayer H. Architects, LIE, 1997; thermosensitive bed-sheets with data protection-pattern on cotton. Photography by Christina Dimitriadis

In the present decade, architectural body talk has taken center stage once again, whether motivated by racial-justice movements, COVID, or (dis)embodied tech. In 2019, New York performance-art biennial Performa brought out Bodybuilding: Architecture and Performance, “the first publication to examine the use of live performance by architects,” which posits, among other things, that the 2007–08 financial crash drove architects to work on their own bodies rather than build costly things that nobody could pay for. The following year, in an academic vein, Routledge released Architecture and the Body, Science and Culture, which promised a cross-historical look at its titular themes, its promotional copy explaining that “[b]y adding the third factor — science — to the architecture and body equation … [t]his book spatializes body theory and ties it to the experience of the built environment in ways that disturb traditional boundaries between the architectural container and the corporeally contained.”

Mayer H., who is set to revisit heat-sensitive seating elements and his Data Protection wallpaper in a 2024 exhibition in Los Angeles, notes that in his early career he “had to come to an ambivalent practice between artwork, installation, larger spaces, and buildings.” One throughline — evident in his temperature-sensitive LIE bed sheets (1997) as well as in built projects such as Metropol Parasol in Seville (2004–11) — is an attention to “weather as an activator for everyday life.” Light and shadow, heat and cold — seeing buildings react to bodies enjoins us to remember how our bodies relate to built environments and the shifting climate.

Meanwhile, Diller’s firm continues to engage the body in direct ways, such as in her 2019 line for Prada, DS+R’s design for the Met’s Heavenly Bodies (2018), and the visual environment for Bill T. Jones’s Deep Blue Sea Armory performance (2021). She says critiques around the body led to critiquing “conventions, whether they’re at the scale of the institution or the body, the scale of a drinking glass or a city.”

Princeton, a hotbed of last century’s body talk, now features an Embodied Computation Lab for robotics-focused architectural research, where, in 2019, Princeton professor and Black Box Research Group director V. Mitch McEwen hosted the Black Imagination Matters symposium, which invited investigations into architecture, performance, visibility, and technology in the context of race. Events included a sonic performance lecture by Gooden in which he repeated lines including, “You’re composing images with your body,” and architect Amina Blacksher jumping rope with cutting-edge robots.

The Rotary Notary and His Hot Plate, 1987. Body Armor. Courtesy of Diller + Scofidio. Photo by Michael Moran.

Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s Meat Dress was created to enter the 2006 Miss Meatpacking District Gown Contest in New York City. It was inspired by the formerly fringe neighborhood’s history as an intersection of the meat industry and leather bars and comprised a bodice of woven raw bacon and a skirt of stitched pastrami. Photography by Diller Scofidio + Renfro.

The Rotary Notary and His Hot Plate, 1987. Juggler of Gravity. Photo by Michael Moran.

Still at Princeton, Colomina has continued her corporeal investigations with the book X-Ray Architecture (2019), while Lyra Kilston released the similarly themed Sun Seekers: The Cure of California that same year. Both biological art — such as Jes Fan’s hormone-filled glass orbs at the 2022 Venice Art Biennale — or Cruising Pavilion, a gay architecture curatorial project begun in 2018, have been resurgent centerpieces in galleries and biennials, while in other practices, such as architect Upali Nanda’s, neuroscientific experimentation has begun to play a bigger role in design, especially for schools and hospitals. Increasing awareness (and measurability) of environmental health is shaping interiors, the pandemic having ushered in a bigger conversation around air quality and pathogens, and their spatial management.

It’s to be hoped that the pandemic also served as an enjoinder for architects to put design for physical disability at the core of their work. Proposed and actual solutions range from rethinking ventilation and fenestration to designing algorithmic capacity tracking, the ethos of microbe-conscious planning, thoughtful circulation of air and people, and clear communication design, which could serve to make spaces safer and more navigable to more people. At another level, it reminds us that disabilities are partially constructed by unnecessary built-in physical limitations, and that architects play a huge role in creating or limiting access by mediating movement, sense, and even disease.

You could say history is repeating itself, but in architecture and beyond we continue to find new metaphors and frameworks to navigate our relationship to our bodies — mechanized, digitized, or otherwise. Importantly, says Ricco, “no one uses the single definitive form of ‘the body’ anymore, opting instead for an understanding of ‘bodies’ in the plural.” Whatever the status of “the body” in arcane books or biennials, whether self-aware or not, architecture is a project not just of “the body”but of and for bodies — an organization of human relations with respect to space, place, the non-human, and each other.